Several months ago, I had a pretty comprehensive discussion with a Dutch colleague, Theo Tomassen, who had sent me questions regarding my general procedures as a captioner. Seeing as how there is very little material on stenography on the Internet in the Dutch language, I thought I’d share his questions and my responses on my blog. It is still not complete as Theo is working on his responses to my questions I posed in response but I will post a follow-up as soon as I have them! What follows is completely in Dutch. If you don’t speak Dutch but would like to know what was said, there’s always Google Translate :]. Also, please keep in mind that Dutch is not my native tongue.

Een paar maanden geleden, had ik een hele uitgebreide discussie met een Nederlandse collega, Theo Tomassen, die stuurde mij een aantal vragen over mijn algemene procedures als schrijftolk. Aangezien het gebrek aan publicaties hierover in de Nederlandse taal op het internet, heb ik besloten om zijn vragen en mijn antwoorden op mijn blog te delen. Het is nog niet klaar want ik wacht op Theos antwoorden naar aanleiding van mijn vragen maar ik post ze hierop zodra ik ze heb! Het navolgende is compleet in Nederlands. Als je geen Nederlands spreekt en je wilt graag even weten wat er gezegd werd, is er natuurlijk altijd Google Translate :]. Bovendien, hou er rekening mee dat het Nederlands niet mijn moedertaal is.

THEO: Mijn belangrijkste vraag is wat langer, die moet ik even inleiden. Deze heeft betrekking op finger spelling. Ik heb je verteld dat ik voor Nederlands werk als gediplomeerd schrijftolk (“CARTer”) voor doven en slechthorenden. De vraag naar Engels is groot, maar er zijn maar weinig schrijftolken die dat willen/kunnen. Echter, het Engels wordt vaak gesproken door Nederlanders. Dit betekent dat er regelmatig Nederlandse instellingen, plaatsnamen, namen van personen worden genoemd die uiteraard niet in mijn dictionary staan.

STANLEY: Dat is geweldig te horen! Ik vond Amsterdam heel, heel prachtig wanneer ik deze zomer op bezoek was. Ik begon over te denken de mogelijkheid van misschien daarheen verhuizen en werken maar voor nu, geniet ik van het leven in New York. In Januari, woon ik hier pas twee jaren. Ik kom oorspronkelijk uit Seattle.

THEO: Stel dat een spreker zou zeggen: “Ladies and gentlemen, I should now like to give the floor to Theo Tomassen, president of the Nederlandse Schrijftolken Vereniging.” Ik weet niet zeker of het praktisch om dergelijke woordklonten steeds allemaal te vingerspellen op de Diamante. Ik weet dat Stenograph een QWERTY-toetsenbord heeft dat je op de Diamante kan bevestigen. Ik kan heel snel typen op QWERTY, die snelheid zal ik nooit halen op de Diamante.

STANLEY: Wat mij betreft, zou ik nooit een extern toetsenbord gebruiken. Je zou wat heel tijd vergen voor wisselen tussen de beide als je moet dat vaak doen.

THEO: Vraag dus: is het een rare werkwijze om te wisselen tussen de Diamante en dat toetsenbord in dergelijke gevallen? Ik snap dat dit op een snelheid van 230 woorden per minuut misschien lastig is, maar in Nederland onderbreken de tolken de spreker als ze op dit soort abnormale snelheden praten.

STANLEY: Zoals ik al zei: Ik zou alleen op het klaarmaken (prep) en op fingerspelling vertrouwen voor woorden die ik niet in mijn woordenboek heb.

THEO: Als je aan het CART’en bent en er valt een woord waarvan je sterk het vermoeden hebt dat het niet in je woordenboek staat, vingerspel je dat dan of kies je een synoniem?

STANLEY: Bijna altijd fingerspelling. Ik zou een synoniem kiezen alleen als ik geen andere keuze heb (bv, de spreker gaat te snel of ik kon niet het precies woord horen).

THEO: Schrijf je tijdens het CART’en alle hoofdletters —

STANLEY: Nee. Mixed case, altijd ;].

THEO: contractions voor “he’s” en dergelijke?

STANLEY: Ik probeer doorgaans, een echte woordelijk verslag te maken dus schrijf ik, alles, zo veel mogelijk, precies hoe ik het heb gehoord, zelfs wanneer wat de spreker zegt is formeel niet goed Engels. Als hij “‘cause” zegt ipv “because”, dat is wat ik in de transcriptie zet. Want deze (in tegenstelling tot situaties in de rechtbank) zijn geen officieele verslagen, is het niet noodzakelijk altijd aan formele grammaticaregels te houden.

THEO: Als bijvoorbeeld een instelling “City Health Care” heet en het tempo is voor mij hoog, schrijf ik “city health care”. Ik weet dat er een Case CATalyst een aanslag is om bijvoorbeeld de vorige drie woorden een hoofdletter te geven, maar het is toch allemaal weer bagage.

STANLEY: Ja, doorgaans als de snelheid is te hoog, zorg ik me niet zo veel over kleine details zoals hoofdlettergebruik. Het belangrijkste ding op dat moment is alle de woorden krijgen.

Als het mogelijk is, je moet gebruiken alleen macros die veranderingen maken voordat de text verzonden wordt. Met andere woorden, gebruik functies die het volgend woord een hoofdletter geeft (en niet het vorig). Met meeste systemen zoals Text-On-Top of broadcast encoders, je bewerkingen zullen niet weerspiegeld worden als je probeert naderhand veranderingen te maken. Laat me eens weten als je dit niet begrijpt.

THEO: Heb je bepaalde dingen in je dictionary gedefinieerd die bij het CART’en enorm handig zijn en tijdwinst opleveren?

STANLEY:

- Een stroke voor het toevoegen van definities.

- Gemeenschappelijke symbolen zoals @, $, _, %, <, >, <=, >=, -, –, =, !, daarnaast Griekse letteren, en definities voor Spaanse en Duitse letteren: á, é, ë, ä, enz. Ik heb zelfs alle de emoji gedefinieerd.

THEO: Wat is jouw mening over briefs? Als ik op de Facebook-pagina Supporting Court Reporter Students kijk, zie ik dat veel mensen voor de meest gekke termen een brief vragen. Termen die je niet zo vaak tegenkomt. Natuurlijk leveren briefs tijdwinst op, maar ik briefs voor zeldzamere termen onthoud ik toch niet.

STANLEY: Als ik moet een woord of zin meer dan twee keer schrijven, dat bestaat uit meer dan twee toetsenaanslagen, maak ik een brief. Ik heb weinig of geen probleem om veel briefs te memoriseren maar ieder mens is uniek qua talent dus ik denk dat je moet doen wat is voor jou de makkelijkste.

Ik wil je laten weten dat je moet niet alles wat je leest op die pagina serieus nemen. Hoewel er goede en handige informatie is, zit er heel veel advies dat het niet waar is, gebaseerd op ouderwetse meningen. Je moet altijd je eigen oordeel vormen nadat je een aantal mensen geraadpleegd hebt.

THEO: Zijn er dingen die je op de opleiding voor court reporter leert, maar die je werkelijk nooit zult toepassen in CART? Ik denk bijvoorbeeld aan “8 o’clock”. Dat zou je dan moeten schrijven als “8:00 o’clock”. Nu heb ik in mijn dictionary aanslagen gedefinieerd als /8 /KHRBG, dat wordt dan “8:00 o’clock”. Maar vanuit CART gezien vind ik het een beetje van de zotte om in alle gevallen aan een hypercorrecte schrijfwijze vast te houden. Of zie je dat anders?

STANLEY: Ik heb geen ervaring met in de rechtbank werken dus ik voel me niet bevoegd/gekwalificeerd om deze vraag te beantwoorden.

THEO: Een beetje aansluitend op vraag 6: heb je misschien nog suggesties hoe ik mijn speedbuilding-traject zou kunnen aanpakken?

STANLEY: Je moet met verscheidene materialen oefenen. Wat is belangrijkste is niet te vervelen. Ik luisterde vaak naar de uitzendingen van howstuffworks.com. Ze zijn vrij op iTunes om te downloaden. Vind inhoud waarin je bijzonder geïnteresseerd bent. Je hoeft niet naar dezelfde saaie drills opnieuw en opnieuw luisteren. Kies, bv, een Engelse televisieprogramma of radioprogramma dat je leuk vindt en doe dat maar.

THEO: Ik zal nooit in mijn leven werk doen dat op court reporting lijkt, maar begin straks gelijk met CART’en. Het heeft voor mij dus geen zin om een heel goede court reporter te worden die niet kan CART’en: stel dat een snel gesproken tekst over “Chicago” gaat en ik heb geen brief daarvoor. Ik kan zou dan als court reporter telkens een “C” kunnen aanslaan, want ik onthoud wel dat het om “Chicago” gaat. Maar als CART’er kom ik daar niet mee weg. Ik moet/wil dus nu al op CART-kwaliteit studeren: de output moet een volledig leesbare tekst zijn, waarbij ik uiteraard een paar fouten wel accepteer. Maar een hele reeks untranslates die nog wel te lezen zijn voor een court reporter, slaat natuurlijk nergens op voor CART’en.

STANLEY: Ja, dat is heel onaanvaardbaar voor schrijftolken. Je moet voor de eerste keer, de woord dat bestaat niet in je woordenboek fingerspellen en laat de software je een briefsuggestie geven. Wanneer je een moment hebt, maak je dan een definitie die ga in je dict te blijven.

THEO: Zijn er nog bepaalde realtime-instellingen in Case CATalyst die ik beslist goed moet bekijken omdat ze handig zijn? Misschien gebruik je Eclipse of iets anders, maar ik denk dat er veel functies zijn die elkaar veel overlappen?

STANLEY: Kun je hier, specifieker zijn?

THEO: Welke setup gebruik je om de tekst draadloos door te sturen naar bijvoorbeeld een tablet van een klant? Case CATalyst heeft nu CASEview, maar de licentie daarvan ik niet echt goedkoop. En ik moet volgens mij een wifi-verbinding hebben, wat ook niet overal mogelijk is.

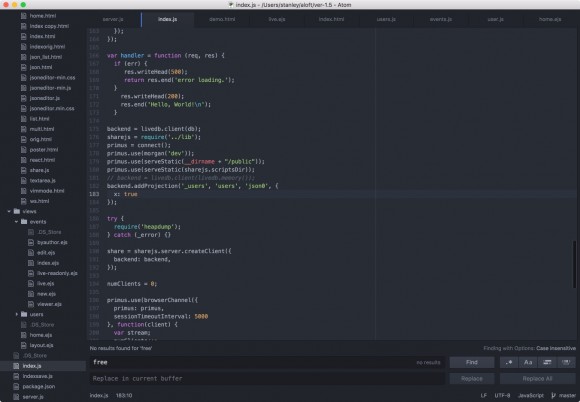

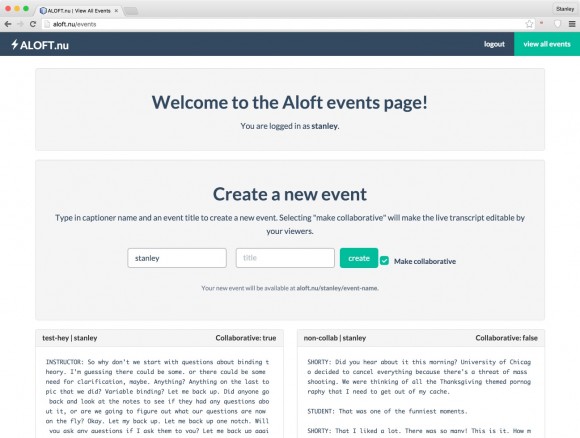

STANLEY: In het verleden, ik gebruikte de vrije versie van Bridge maar ik heb onlangs een programma geschreven die voert deze functie uit! Bovendien is het vrij (voor nu). Je kan mijn niet-zo-korte beschrijving op mijn website lezen. http://blog.stanographer.com/aloft.

THEO: Voor mijn Nederlandse werk gebruik ik Text On Top voor een draadloze verbinding. Die kan ik ook met Case CATalyst gebruiken, maar de lay-out wordt dan niet overgenomen. Als ik een Enter geef, gebeurt er niets op het scherm van de klant. De ontwikkelaar heeft uitgelegd waarom dat zo is, gaat wat ver om dat allemaal uit te leggen. Maar het is wel zo.

STANLEY: Ik denk dat er een instelling is voor “verbatim mode” of zo waarbij je moet ctrl + enter drukken om een nieuwe lijn te maken en niet gewoon enter. Maar ik gebruik CC niet, dus ik weet niet wat zou dat gedrag kunnen veroorzaken.

THEO: Ik heb je videoblog over de Lightspeed gezien. Is het iets om te overwegen?

STANLEY: YES! I LOVE IT! Heb je specifieke vragen erover? Mijn god, ik kan niet langer in deze taal praten. Haha.