I often make the analogy that trying to be a polyglot in an English-speaking country is like trying to maintain a hobby for keeping igloos somewhere non-polar. Without year-round cold, you either have to keep adding snow, or watch in resignation as your bespoke collection of icy enclosures melt away.

Language atrophy happens especially quickly for us English speakers because everywhere, it’s hot. It’s far more likely the person you’re talking to can speak English better than you can speak their native language or they underestimate your abilities. So chances are that unless you’re already super fluent in another language, whenever you try to practice it, you’ll very likely get a, “Wow! Your [insert language] is very good!” and the interaction will resume in English. (Ugh.) And even though I live in New York City, it’s still an effort to keep all of my igloos from turning into puddles of mush.

So I keep adding snow every day (i.e. artificially force exposure to all my languages constantly). Like a good polyglot, I have Google Translate on the first page of my iPhone’s home screen. Whenever I have random moments of pause throughout the day when I realize, “Wait. How would you say [word/phrase] in [language A]?” I’ll stick it into Translate for a quick answer.

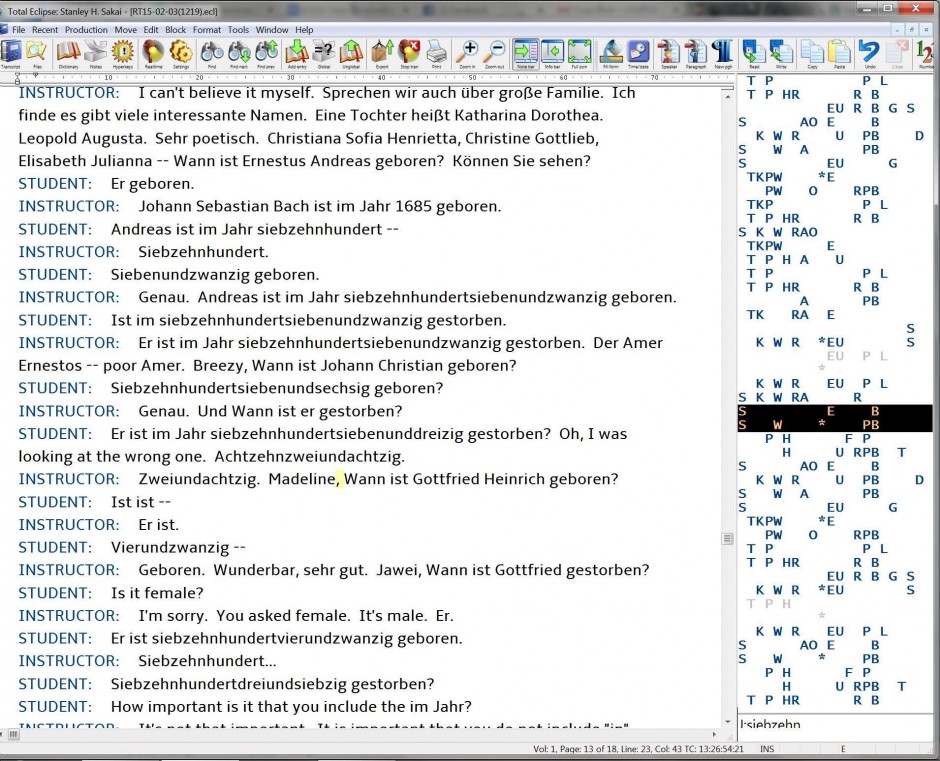

But wait. I’ve also just realized I don’t know how to say that in B, C, D, or E! Okay. Hit X. Select B. Cool. Hit X. Select C. Cool. Hit X. Select D… this quickly gets tiresome because each time, you have translate each one manually. The Google Translate app only keeps a history of your five last-translated languages.

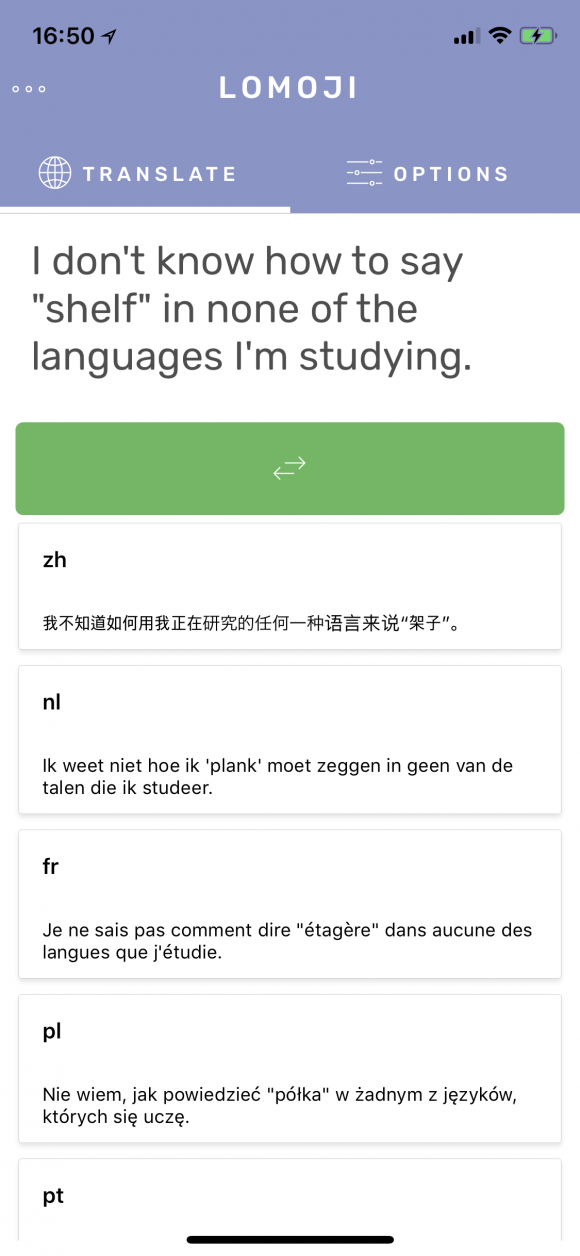

As we polyglots tend to, I “dabble” quite a bit — enough to notice how frequently I was having to scroll back to that huge list even for my most-used languages. On a random day when I wanted a reminder of how to say “shelf” in Spanish I had to manually select from the master list it because it had gotten bumped off the last-used list by random forays into Danish and Portuguese.

I wanted something where I could select ALL the languages I’m currently “dabbling” in so I could view translations for all of them concurrently. Well, I had never implemented the Google Translate API in anything before, so I took this as a learning opportunity. I went ahead and created myself an account on Google Cloud Console, got myself an API key, and started playing.

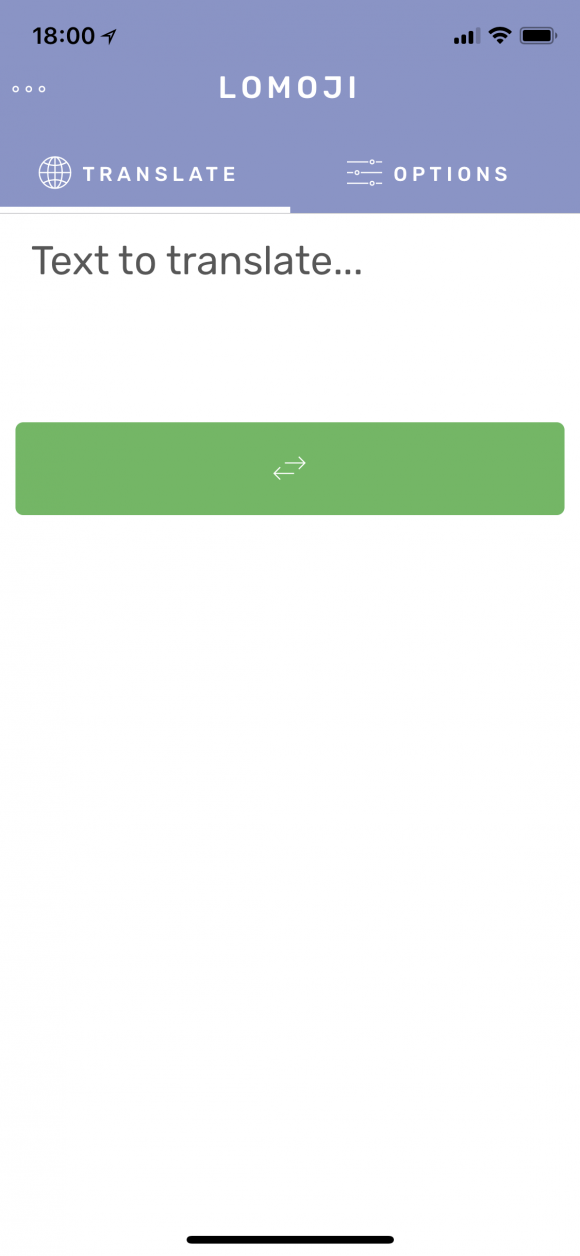

The result is Lomoji.

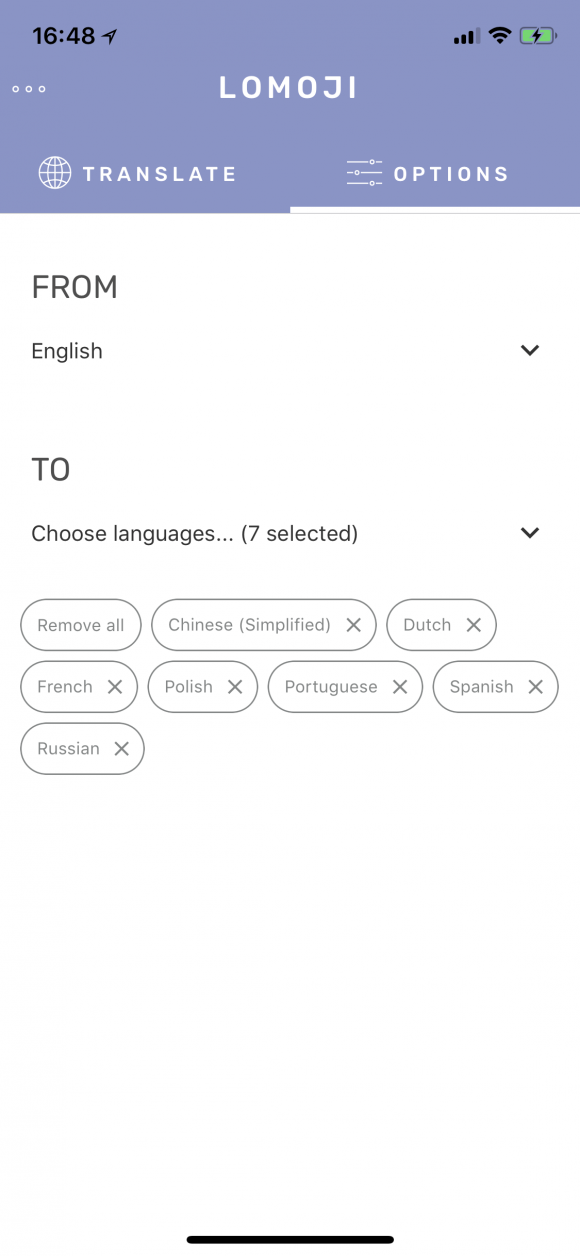

Lomoji is a small React Native app that lets you select multiple target languages, and persist them in AsyncStorage so that whenever you perform a translate action, with just a quick glance, you’re instantly reminded of how to say them in all your languages. The languages only disappear when you uncheck them; not because you happened to translate a few small things in five other languages prior.

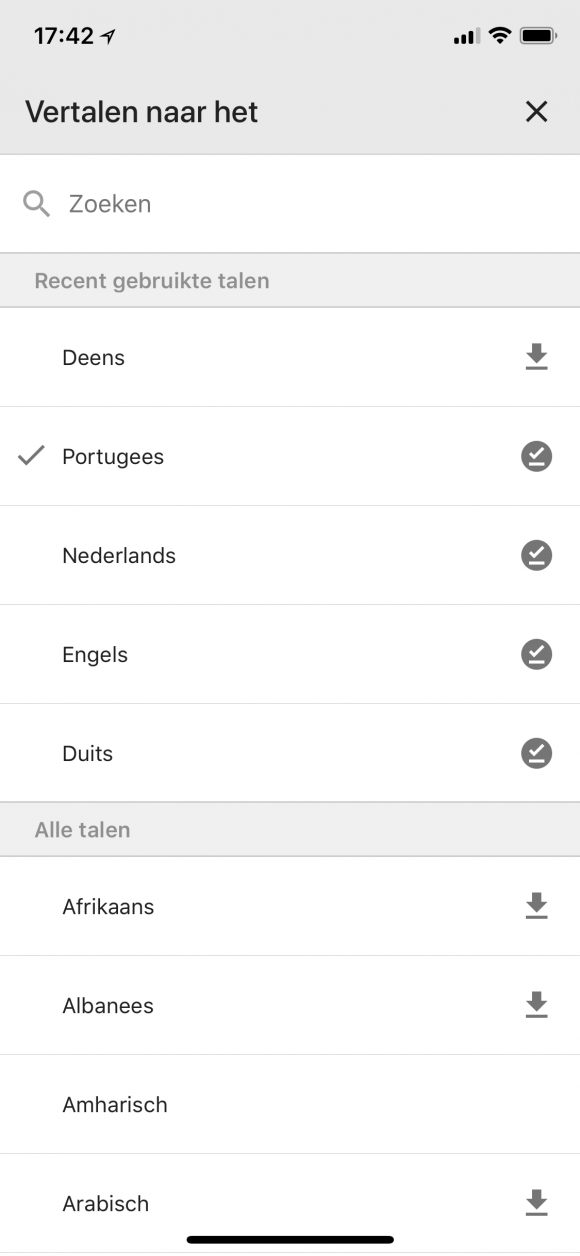

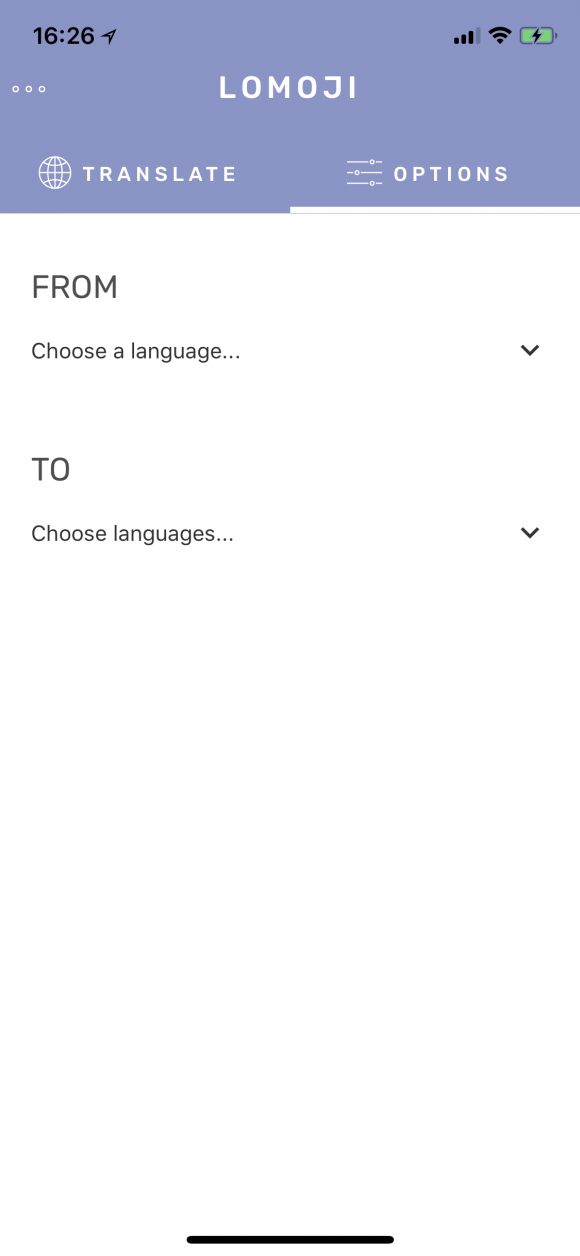

First select the language you want to translate from…

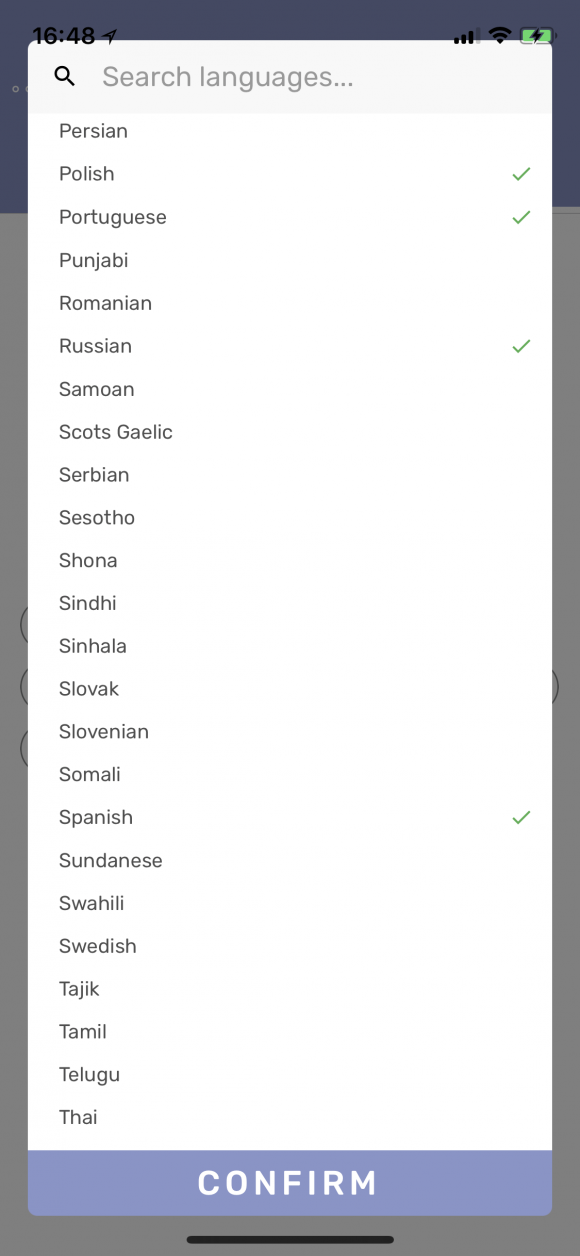

Then select your destination language(s)…

After hitting “confirm,” we have our nice list of igloos!

Enter the string to be translated and… voilà!

THAT’S WHUT I’M TALKIN’ ABOUT.

Google Translate makes it easy to get an updated list of all available languages. As noted in their documentation, you just make an API request that Translate responds to with a JSON object to get the most up-to-date list. So I made the component so that it asynchronously checks the list of available languages, and updates the internal list before defaulting to loading the in-built store of languages in case that fails. This makes it future-friendly as support for languages are added (or perhaps removed) by Google.

async componentDidMount() {

await axios

// Get most recent list of langs from Google.

.get(`https://translation.googleapis.com/language/translate/v2/languages?key=${config.apiKey}&target=en`)

// If that was successful, set our internal state.

.then((result) => {

this.setState({

langList: result.data.languages

});

})

// If that fails, use default built-in list of languages.

.catch((err) => {

this.setState({

langList: languages.data.languages

});

alert(`Unable to retrieve list of languages from Google Translate.\nLocal list used instead.\n\n${err}`);

});

this.setState({assetsLoaded: true});

}But that’s it for now! I think in a future iteration, it would definitely make for a more fluid user experience if the input language were detected automatically. Still a few loose ends to tie up but I was too excited not to not post about it. I’ll update as I move toward publishing it!

Oh, and if you’re wondering why I decided to call it “Lomoji,” it’s because in Korean, “X (eu)ro muoji” (X[으]로 뭐지?), where X is a language, is a phrasal suffix that roughly translates to, “How would you say it in X?” I simplified it and anglicized it to make it catchy to Western ears.

So “Yeongeo ro muoji?” (영어로 뭐지?), where “yeongeo (영어)” is “English,” would translate to, “How would you say that in English?” Clever?

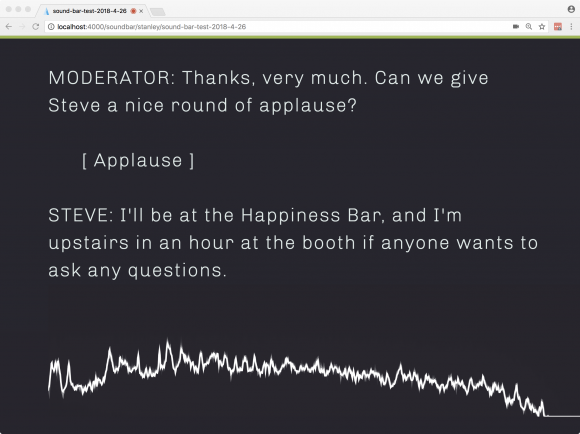

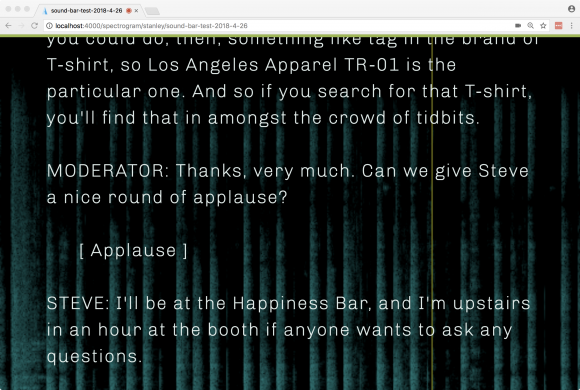

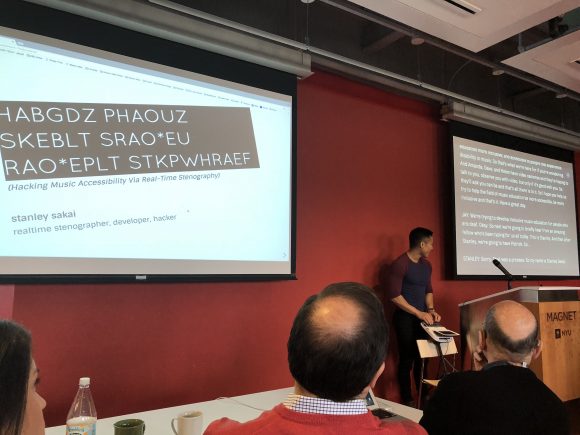

![On screen, it shows a bunch of dialogue and then parentheticals for [ Big Room House/EDM ] and [ Tiësto, Martin Garrix - "The Only Way Is Up" ].](http://blog.stanographer.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/C4_7WA5XAAEf-A8-580x363.jpg)