After reading this lovely article by Kelley Lord wherein she describes the struggles associated with her experiences as a server in a cruel world, I was inspired to come up with a similar list, but having to do with stenographers, of course! I realize that stenographers are a fairly esoteric bunch — “misunderstood” doesn’t even begin to cover it. So it seemed to be a fitting theme for a blog post. As a disclaimer, I’m writing this from the viewpoint of a realtime captioner. Court reporters work under slightly different circumstances and I won’t delve really into the differences.

Without further ado, Reporters, Not Recorders: 5 Things Your Stenographer Wished You Knew

1. Don’t call what we do “typing.”

Many people make the false assumption that what we’re doing behind our funky little keyboards is essentially listening carefully and “typing” what we hear. Easy, right? In reality, it is far more complex. Typing involves recalling a word’s spelling, tapping out the correct sequence of letters, hitting the space bar and shift keys occasionally, and managing to not get your thumbs lodged in your anus during said process. God help you if you happen to spill your coffee in your lap and you have to backspace the mistakes you made while fumbling, trying to pick your doughnut up off the floor.

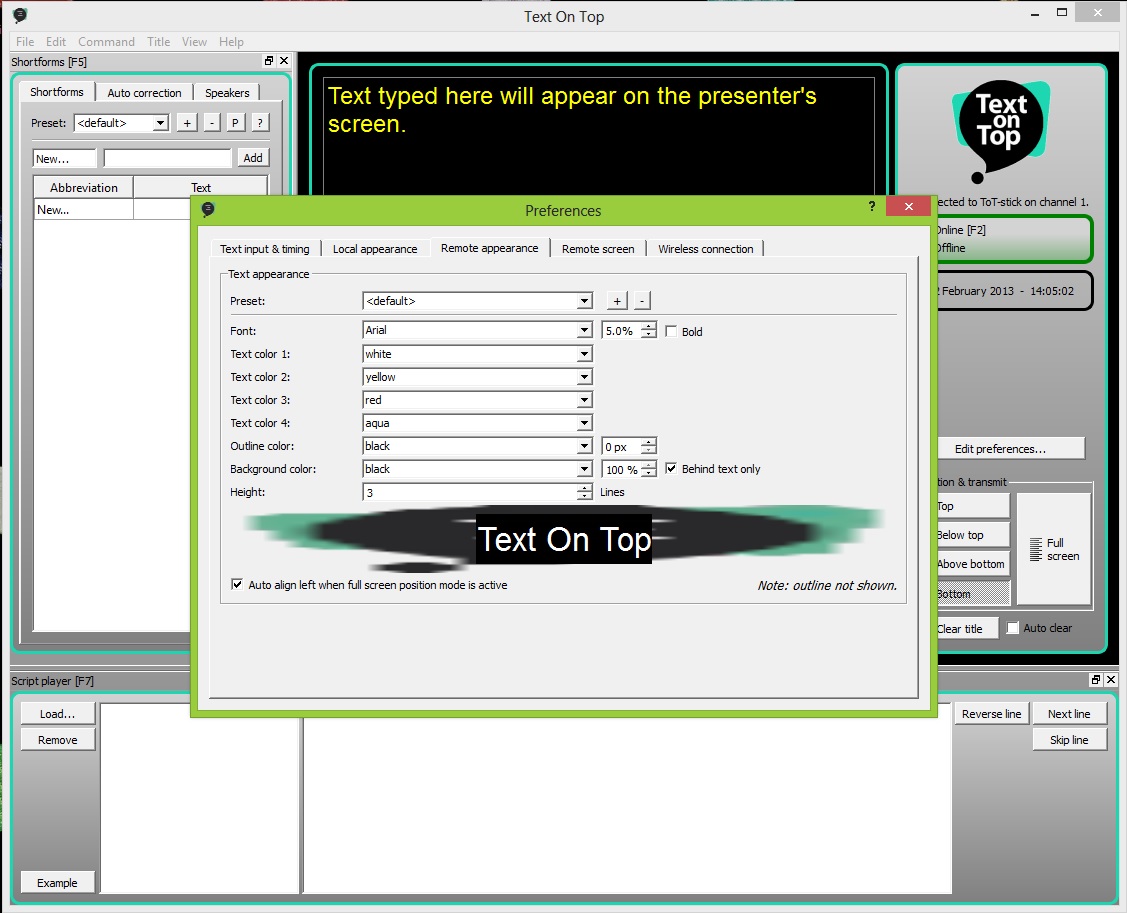

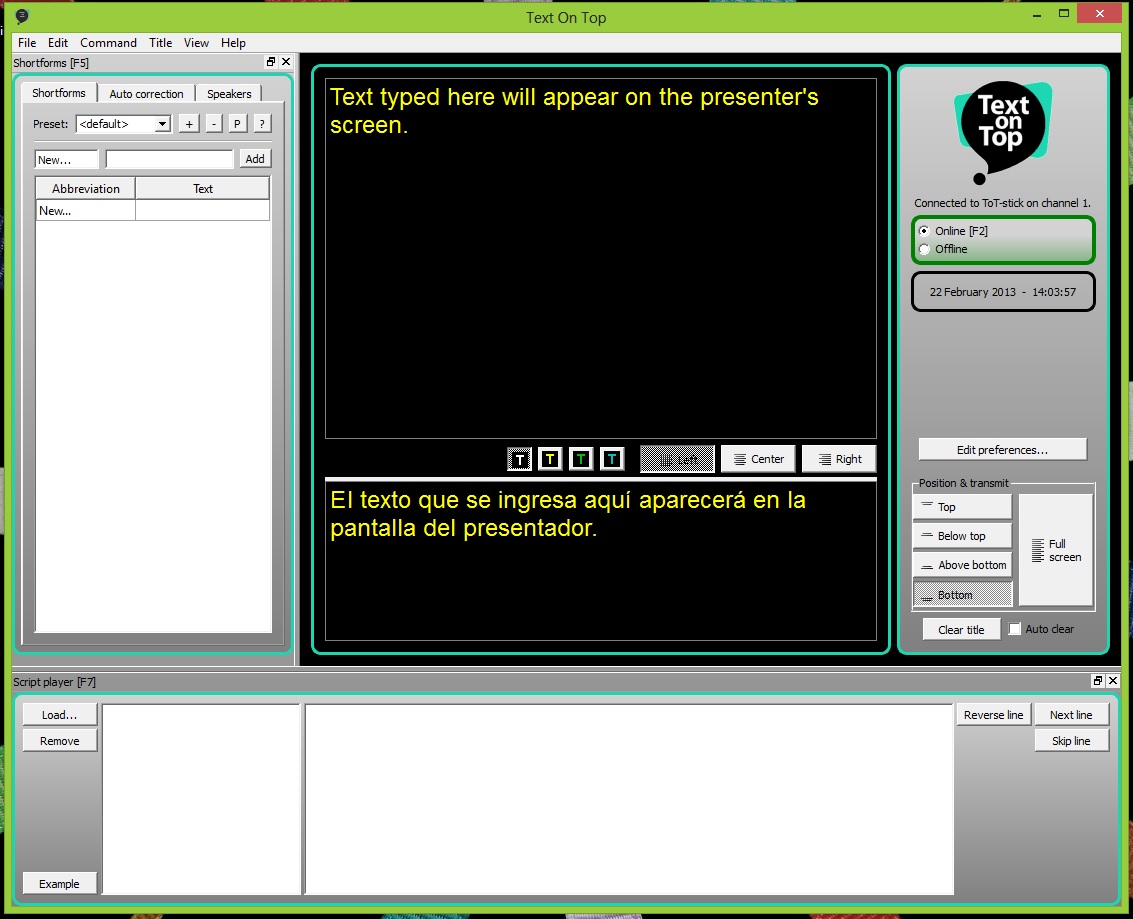

Now as stenographers, we don’t have time to drop our doughnuts or make errors as our job requires us to keep up with somebody else’s speech. That changes the paradigm a bit since now, you’re not only having to get it all down correctly the first time, but you’re having to do it as fast as somebody who isn’t you decides to deliver it. Not to mention, the process of writing steno requires that we hear a phrase, break it down to its constituent words, recall the corresponding shorthand outlines (which look like gibberish to you normal folk), execute those outlines with nearly 100% precision on a completely unique keyboard layout in order for the computer to correctly match them against our personal dictionaries, all at around speeds of two to five syllables per second. This is how it looks in action. We press multiple keys at once to capture handfuls of phonemes at a time, forming entire syllables every time we press down. There is no magic auto-correct or any form of predictive entry, auto-complete, Siri voodoo nonsense. Some modern steno software have algorithms that will try to guess, phonetically or statistically, how sloppy or otherwise malformed steno should have translated but worthy stenographers cannot and do not rely on this. Good realtime (instantly readable, machine-translated steno) is the product of quick and nearly perfect recollection and execution of the entries in one’s personal dictionary. I liken our job to sitting in front of a piano and having someone constantly put new pieces you’ve never seen before in front of you, demanding you play them at full concert speed with 99% accuracy. The preferred terms when referring to a working stenographer are “writing” (from “writing shorthand”) or “stenoing.” So please don’t refer to what we do as “typing” as it would be a shame if you were to trip and fall over a strategically misplaced piece of equipment before the end of the proceeding.

2. We’re not robots and we’re not psychic.

As Dee Boenau puts it, “we [stenographers] have to be very worldly” in that our work requires us to competently take down conceivably any topic thrown at us. We’ll try our best if you unexpectedly delve into the works of Feyerabend, discuss the plausibility of a working Alcubierre Drive, or on a whim, prattle your way into Sorites’ Paradox, GroEL/GroES, the P1-N1-P2 complex, maybe the historical significance of Nyan Cat, or the current exchange rate of the Dogecoin. But we can’t know everything all the time and the occasional error is bound to happen. And although most of us practically become walking, breathing encyclopedic databases of random knowledge over a career span, realize that we are still not Watson and giving us a list of key terms beforehand is immensely helpful. You see, what we stenographers do is we program shortcuts into our steno lexicons in advance so that we can pop out anticipated phrases or terminology quickly, usually via a single-stroke shortcut that we come up with on the spot. So even for what seems “basic” to you, giving us a heads-up for little things like, “Oh, by the way, Jacqui sitting on the left spells her name J-A-C-Q-U-I and her last name is Kaminsky” or “We’re going to be talking a lot about indigenous fauna, like x, x, and x” takes a HUGE load off our shoulders as we can then go ahead and redefine our steno outline for “Jackie” to render with her preferred spelling and quickly stick in briefs for “indigenous” and “fauna” to have on hand as they come up. It just makes things go a lot smoother for us. As the person who makes your dialogue magically appear in text form next to your PowerPoint for everyone to see, I have a lot of power. But with great power comes great responsibility and I will thrust part of that responsibility onto you, speaker and/or event organizer, of ensuring the captioner is informed of any tricky names or terminology. If we flub something due to your failure to inform us and something funny goes up on the big screen, I’m just going to go ahead and say, “Nice job, idiot. It’s all your damn fault.” ;]

3. Stop talking over each other!

I have a little exercise for you. Type me a verbatim transcript of this eight-second audio clip taken from a VSauce video.

Got it? Cool. Assuming you have normal hearing, a working short-term memory, can type, have a computer that can play the clip, and understand English, it shouldn’t be too difficult.

Now transcribe this one.

Wasn’t that fun? Now imagine doing that for two hours.

One at a time or I torch this mother to the ground with your motor mouth in it, k? Thx.

4. Remember to breathe and enunciate.

The average, non-cocaine-abusing English speaker speaks at a rate of around 150-180 WPM. 180 WPM sounds like a pretty comfortable pace to most native speakers. The baseline requisite speed to become a certified stenographer in the United States is generally set at 225 WPM for English at 95% accuracy. The best of us can go much higher than that, sometimes exceeding 300 or more WPM in bursts. So, yes, as licensed stenographers, we are trained to go FAST. But please, give us a break and slow down once in a while. Maybe add in some tasteful pauses?

Now I understand it isn’t easy to change your speaking habits. I find that most speakers are completely unaware that the way they speak is, well, really quick, and that they’ve had their foot planted firmly on the stenographer’s submerged head for the past two hours. And even after a polite reminder to maybe slow down, most people relapse after about ten minutes and it gets awkward having to repeatedly remind people to monitor their speech as people tend to become very self-conscious. So if you could maybe remember this and possibly, pretty please, with a cherry on top kick it down two notches and try to make an effort to keep it there? But more than just unrelenting speed, the number one thing that makes me want to drown the speaker I’m taking down in the river of blood from my rage-induced fit of harakiri is mumbling. I can go fast but if I have to strain to understand what you’re saying, those split seconds of hesitation add up and REALLY make it a struggle for me to maintain a rhythm. Oh, and if you’re talking so fast that you start mumbling because you physically can’t pronounce the words that quickly without getting your tongue caught in the ceiling fan? Yeah, I hope as you’re drowning in that river of blood, you trip over the strategically-misplaced tripod into a bed of rusty nails covered in cat urine.

5. A little acknowledgement never hurt.

Please, do take the time to talk to us. We’re friendly, most of the time and — surprise! — people, too. After working behind the scenes for so long, Norma and I were really spoiled by you wonderful folks at SRCCON. It was a welcome and unexpected novelty as stenographers to be put front and center for the entirety of the conference. We really appreciated it and we joked amongst ourselves that our heads would never return to normal size. But really, just asking how we’re doing or if there is anything you could do to help make our lives easier is appreciated. We don’t ask for much. Give me a comfortable, armless chair, an extension cord, and maybe a few snacks and we good. Anything beyond that is extra but for us stenographers, the distance between “apathetic” to “LOVING YOU” is small and any effort on your part will win us over and cause us to casually kick that tripod back under the table :].