Hey, everybody! So due to popular request, I just uploaded a new vlog post today demoing my Spanish steno! Check it out!

Category: Uncategorized

Vragen Van Theo

Several months ago, I had a pretty comprehensive discussion with a Dutch colleague, Theo Tomassen, who had sent me questions regarding my general procedures as a captioner. Seeing as how there is very little material on stenography on the Internet in the Dutch language, I thought I’d share his questions and my responses on my blog. It is still not complete as Theo is working on his responses to my questions I posed in response but I will post a follow-up as soon as I have them! What follows is completely in Dutch. If you don’t speak Dutch but would like to know what was said, there’s always Google Translate :]. Also, please keep in mind that Dutch is not my native tongue.

Een paar maanden geleden, had ik een hele uitgebreide discussie met een Nederlandse collega, Theo Tomassen, die stuurde mij een aantal vragen over mijn algemene procedures als schrijftolk. Aangezien het gebrek aan publicaties hierover in de Nederlandse taal op het internet, heb ik besloten om zijn vragen en mijn antwoorden op mijn blog te delen. Het is nog niet klaar want ik wacht op Theos antwoorden naar aanleiding van mijn vragen maar ik post ze hierop zodra ik ze heb! Het navolgende is compleet in Nederlands. Als je geen Nederlands spreekt en je wilt graag even weten wat er gezegd werd, is er natuurlijk altijd Google Translate :]. Bovendien, hou er rekening mee dat het Nederlands niet mijn moedertaal is.

THEO: Mijn belangrijkste vraag is wat langer, die moet ik even inleiden. Deze heeft betrekking op finger spelling. Ik heb je verteld dat ik voor Nederlands werk als gediplomeerd schrijftolk (“CARTer”) voor doven en slechthorenden. De vraag naar Engels is groot, maar er zijn maar weinig schrijftolken die dat willen/kunnen. Echter, het Engels wordt vaak gesproken door Nederlanders. Dit betekent dat er regelmatig Nederlandse instellingen, plaatsnamen, namen van personen worden genoemd die uiteraard niet in mijn dictionary staan.

STANLEY: Dat is geweldig te horen! Ik vond Amsterdam heel, heel prachtig wanneer ik deze zomer op bezoek was. Ik begon over te denken de mogelijkheid van misschien daarheen verhuizen en werken maar voor nu, geniet ik van het leven in New York. In Januari, woon ik hier pas twee jaren. Ik kom oorspronkelijk uit Seattle.

THEO: Stel dat een spreker zou zeggen: “Ladies and gentlemen, I should now like to give the floor to Theo Tomassen, president of the Nederlandse Schrijftolken Vereniging.” Ik weet niet zeker of het praktisch om dergelijke woordklonten steeds allemaal te vingerspellen op de Diamante. Ik weet dat Stenograph een QWERTY-toetsenbord heeft dat je op de Diamante kan bevestigen. Ik kan heel snel typen op QWERTY, die snelheid zal ik nooit halen op de Diamante.

STANLEY: Wat mij betreft, zou ik nooit een extern toetsenbord gebruiken. Je zou wat heel tijd vergen voor wisselen tussen de beide als je moet dat vaak doen.

THEO: Vraag dus: is het een rare werkwijze om te wisselen tussen de Diamante en dat toetsenbord in dergelijke gevallen? Ik snap dat dit op een snelheid van 230 woorden per minuut misschien lastig is, maar in Nederland onderbreken de tolken de spreker als ze op dit soort abnormale snelheden praten.

STANLEY: Zoals ik al zei: Ik zou alleen op het klaarmaken (prep) en op fingerspelling vertrouwen voor woorden die ik niet in mijn woordenboek heb.

THEO: Als je aan het CART’en bent en er valt een woord waarvan je sterk het vermoeden hebt dat het niet in je woordenboek staat, vingerspel je dat dan of kies je een synoniem?

STANLEY: Bijna altijd fingerspelling. Ik zou een synoniem kiezen alleen als ik geen andere keuze heb (bv, de spreker gaat te snel of ik kon niet het precies woord horen).

THEO: Schrijf je tijdens het CART’en alle hoofdletters —

STANLEY: Nee. Mixed case, altijd ;].

THEO: contractions voor “he’s” en dergelijke?

STANLEY: Ik probeer doorgaans, een echte woordelijk verslag te maken dus schrijf ik, alles, zo veel mogelijk, precies hoe ik het heb gehoord, zelfs wanneer wat de spreker zegt is formeel niet goed Engels. Als hij “‘cause” zegt ipv “because”, dat is wat ik in de transcriptie zet. Want deze (in tegenstelling tot situaties in de rechtbank) zijn geen officieele verslagen, is het niet noodzakelijk altijd aan formele grammaticaregels te houden.

THEO: Als bijvoorbeeld een instelling “City Health Care” heet en het tempo is voor mij hoog, schrijf ik “city health care”. Ik weet dat er een Case CATalyst een aanslag is om bijvoorbeeld de vorige drie woorden een hoofdletter te geven, maar het is toch allemaal weer bagage.

STANLEY: Ja, doorgaans als de snelheid is te hoog, zorg ik me niet zo veel over kleine details zoals hoofdlettergebruik. Het belangrijkste ding op dat moment is alle de woorden krijgen.

Als het mogelijk is, je moet gebruiken alleen macros die veranderingen maken voordat de text verzonden wordt. Met andere woorden, gebruik functies die het volgend woord een hoofdletter geeft (en niet het vorig). Met meeste systemen zoals Text-On-Top of broadcast encoders, je bewerkingen zullen niet weerspiegeld worden als je probeert naderhand veranderingen te maken. Laat me eens weten als je dit niet begrijpt.

THEO: Heb je bepaalde dingen in je dictionary gedefinieerd die bij het CART’en enorm handig zijn en tijdwinst opleveren?

STANLEY:

- Een stroke voor het toevoegen van definities.

- Gemeenschappelijke symbolen zoals @, $, _, %, <, >, <=, >=, -, –, =, !, daarnaast Griekse letteren, en definities voor Spaanse en Duitse letteren: á, é, ë, ä, enz. Ik heb zelfs alle de emoji gedefinieerd.

THEO: Wat is jouw mening over briefs? Als ik op de Facebook-pagina Supporting Court Reporter Students kijk, zie ik dat veel mensen voor de meest gekke termen een brief vragen. Termen die je niet zo vaak tegenkomt. Natuurlijk leveren briefs tijdwinst op, maar ik briefs voor zeldzamere termen onthoud ik toch niet.

STANLEY: Als ik moet een woord of zin meer dan twee keer schrijven, dat bestaat uit meer dan twee toetsenaanslagen, maak ik een brief. Ik heb weinig of geen probleem om veel briefs te memoriseren maar ieder mens is uniek qua talent dus ik denk dat je moet doen wat is voor jou de makkelijkste.

Ik wil je laten weten dat je moet niet alles wat je leest op die pagina serieus nemen. Hoewel er goede en handige informatie is, zit er heel veel advies dat het niet waar is, gebaseerd op ouderwetse meningen. Je moet altijd je eigen oordeel vormen nadat je een aantal mensen geraadpleegd hebt.

THEO: Zijn er dingen die je op de opleiding voor court reporter leert, maar die je werkelijk nooit zult toepassen in CART? Ik denk bijvoorbeeld aan “8 o’clock”. Dat zou je dan moeten schrijven als “8:00 o’clock”. Nu heb ik in mijn dictionary aanslagen gedefinieerd als /8 /KHRBG, dat wordt dan “8:00 o’clock”. Maar vanuit CART gezien vind ik het een beetje van de zotte om in alle gevallen aan een hypercorrecte schrijfwijze vast te houden. Of zie je dat anders?

STANLEY: Ik heb geen ervaring met in de rechtbank werken dus ik voel me niet bevoegd/gekwalificeerd om deze vraag te beantwoorden.

THEO: Een beetje aansluitend op vraag 6: heb je misschien nog suggesties hoe ik mijn speedbuilding-traject zou kunnen aanpakken?

STANLEY: Je moet met verscheidene materialen oefenen. Wat is belangrijkste is niet te vervelen. Ik luisterde vaak naar de uitzendingen van howstuffworks.com. Ze zijn vrij op iTunes om te downloaden. Vind inhoud waarin je bijzonder geïnteresseerd bent. Je hoeft niet naar dezelfde saaie drills opnieuw en opnieuw luisteren. Kies, bv, een Engelse televisieprogramma of radioprogramma dat je leuk vindt en doe dat maar.

THEO: Ik zal nooit in mijn leven werk doen dat op court reporting lijkt, maar begin straks gelijk met CART’en. Het heeft voor mij dus geen zin om een heel goede court reporter te worden die niet kan CART’en: stel dat een snel gesproken tekst over “Chicago” gaat en ik heb geen brief daarvoor. Ik kan zou dan als court reporter telkens een “C” kunnen aanslaan, want ik onthoud wel dat het om “Chicago” gaat. Maar als CART’er kom ik daar niet mee weg. Ik moet/wil dus nu al op CART-kwaliteit studeren: de output moet een volledig leesbare tekst zijn, waarbij ik uiteraard een paar fouten wel accepteer. Maar een hele reeks untranslates die nog wel te lezen zijn voor een court reporter, slaat natuurlijk nergens op voor CART’en.

STANLEY: Ja, dat is heel onaanvaardbaar voor schrijftolken. Je moet voor de eerste keer, de woord dat bestaat niet in je woordenboek fingerspellen en laat de software je een briefsuggestie geven. Wanneer je een moment hebt, maak je dan een definitie die ga in je dict te blijven.

THEO: Zijn er nog bepaalde realtime-instellingen in Case CATalyst die ik beslist goed moet bekijken omdat ze handig zijn? Misschien gebruik je Eclipse of iets anders, maar ik denk dat er veel functies zijn die elkaar veel overlappen?

STANLEY: Kun je hier, specifieker zijn?

THEO: Welke setup gebruik je om de tekst draadloos door te sturen naar bijvoorbeeld een tablet van een klant? Case CATalyst heeft nu CASEview, maar de licentie daarvan ik niet echt goedkoop. En ik moet volgens mij een wifi-verbinding hebben, wat ook niet overal mogelijk is.

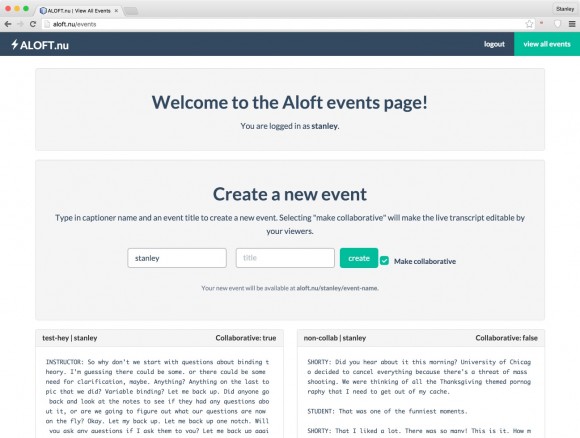

STANLEY: In het verleden, ik gebruikte de vrije versie van Bridge maar ik heb onlangs een programma geschreven die voert deze functie uit! Bovendien is het vrij (voor nu). Je kan mijn niet-zo-korte beschrijving op mijn website lezen. http://blog.stanographer.com/aloft.

THEO: Voor mijn Nederlandse werk gebruik ik Text On Top voor een draadloze verbinding. Die kan ik ook met Case CATalyst gebruiken, maar de lay-out wordt dan niet overgenomen. Als ik een Enter geef, gebeurt er niets op het scherm van de klant. De ontwikkelaar heeft uitgelegd waarom dat zo is, gaat wat ver om dat allemaal uit te leggen. Maar het is wel zo.

STANLEY: Ik denk dat er een instelling is voor “verbatim mode” of zo waarbij je moet ctrl + enter drukken om een nieuwe lijn te maken en niet gewoon enter. Maar ik gebruik CC niet, dus ik weet niet wat zou dat gedrag kunnen veroorzaken.

THEO: Ik heb je videoblog over de Lightspeed gezien. Is het iets om te overwegen?

STANLEY: YES! I LOVE IT! Heb je specifieke vragen erover? Mijn god, ik kan niet langer in deze taal praten. Haha.

Aloft!

First off, apologies for the long radio silence. It’s been far too long since I’ve made any updates! But I just had to share a recent that I’m currently probably the most excited about.

[ Scroll down for TL;DR ]

To begin, a little background. For the past several months, I’ve been captioning an intensive web design class at General Assembly, a coding academy in New York City. Our class in particular utilized multiple forms of accommodation with four students using realtime captioning or sign interpreters depending on the context, as well as one student who used screen sharing to magnify and better view content projected in the classroom. A big shout-out to GA for stepping up and making a11y a priority, no questions asked.

On the realtime captioning front, it initially proved to be somewhat of a logistical challenge mostly because the system my colleague and I were using to deliver captions is commercial deposition software, designed primarily with judicial reporting in mind. But the system proved to be less than ideal for this specific context for a number of reasons.

- Commercial realtime viewing software either fails to address the needs of deaf and hard of hearing individuals who rely on realtime transcriptions for communication access or addresses them half-assedly as an afterthought.

The UI is still clunky and appears antiquated. Limited in its ability to change font sizes, line spacing, and colors, it makes it unnecessarily difficult to access options that are frequently crucial when working with populations with diverse sensory needs. Options are sequestered behind tiny menus and buttons that are hard to hit on a tablet. One of the most glaring issues was the inability to scroll with a flick of the finger. Having not been updated since the widespread popularization of touch interfaces, there is practically no optimization for this format. To scroll, the user must drag the tiny scroll bar on the far edge of the screen with high precision. Menus and buttons clutter the screen and take up too much space and everything just looks ugly.

- Though the software supports sending text via the Internet or locally via Wi-Fi, most institutional Wi-Fi is either not consistently strong enough, or too encumbered by security restrictions to send captions reliably to external devices.

Essentially, unless the captioner brought his or her own portable router, text would be unacceptably slow or the connection would drop. Additionally, unless the captioner either has access to an available ethernet port into which to plug said router or has a hotspot with a cellular subscription, this could mean the captioner is without Internet during the entire job.

Connection drops are handled ungracefully. Say I were to briefly switch to the room Wi-Fi to google a term or check my email. When I switch back to my router and start writing, only about half of the four tablets usually survive and continue receiving text. The connection is very fragile so you had to pretty much set it and leave it alone.

- Makers of both steno translation software and realtime viewing software alike still bake in lag time between when a stroke is hit by the stenographer and when it shows up as translated text.

A topic on which Mirabai has weighed in extensively — most modern commercial steno software runs on time-based translation (i.e. translated text is sent out only after a timer of several milliseconds to a second runs out). This is less than ideal for a deaf or hard of hearing person relying on captions as it creates a somewhat awkward delay, which, to a hearing person merely watching a transcript for confirmation as in a legal setting would not notice.

- Subscription-based captioning solutions that send realtime over the Internet are ugly and add an additional layer of lag built-in due to their reliance on Ajax requests that ping for new text on a timed interval basis.

Rather than utilizing truly realtime technologies which push out changes to all clients immediately as the server receives them, most subscription based captioning services rely on the outdated tactic of burdening the client machine with having to repeatedly ping the server to check for changes in the realtime transcript as it is written. Though not obviously detrimental to performance, the obstinate culture of “not fixing what ain’t broke” continues to prevail in stenographic technology. Additionally, the commercial equivalents to Aloft are cluttered with too many on-screen options without a way to hide the controls and, again, everything just looks clunky and outdated.

- Proprietary captioning solutions do not allow for collaborative captioning.

At Kickstarter, I started providing transcriptions of company meetings using a combo of Plover and Google Docs. It was especially helpful to have subject matter experts (other employees) be able to correct things in the transcript and add speaker identifications for people I hadn’t met yet. More crucially, I felt overall higher sense of integration with the company and the people working there as more and more people got involved, lending a hand in the effort. But Google Docs is not designed for captioning. At times, it would freeze up and disable editing when text came in too quickly. Also, the user would have to constantly scroll manually to see the most recently-added text.

With all these frustrations in mind, and with the guidance of the GA instructors in the class, I set off on building my own solution to these problems with the realtime captioning use case specifically in mind. I wanted a platform that would display text instantaneously with virtually no lag, was OS and device agnostic, touch interface compatible, extremely stable in that it had a rock solid connection that could handle disconnects and drops on both the client and provider side without dying a miserable death, and last but not least, delivered everything on a clean, intuitive interface to boot.

How I Went About It

While expressing my frustrations during the class, one of the instructors informed me of the fairly straightforward nature of solving the problem, using the technologies the class had been covering all semester. After that discussion, I was determined to set out to create my own realtime text delivery solution, hoping some of what I had been transcribing every day for two months had actually stuck.

Well, it turned out not much did. I spent almost a full week learning the basics the rest of the class had covered weeks ago, re-watching videos I had captioned, putting together little bits of code before trying to pull them together into something larger. I originally tried to use a library called CodeMirror, which is essentially a web based collaborative editing program, using Socket.io as its realtime interface. It worked at first but I found it incapable of handling the volume and speed of text produced by a stenographer, constantly crashing when I transcribed faster than 200 WPM. I later discovered another potential problem — that Socket.io doesn’t guarantee order of delivery. In other words, if certain data were received out of order, the discrepancy between what was sent to the server versus what a client received would cause the program to freak out. There was no logic that would prioritize and handle concurrent changes.

I showed Mirabai my initial working prototype and she was instantly all for it. After much fuss around naming, Mirabai and I settled on Aloft as it’s easy to spell, easy to pronounce, and maintains the characteristic avian theme of Open Steno Project.

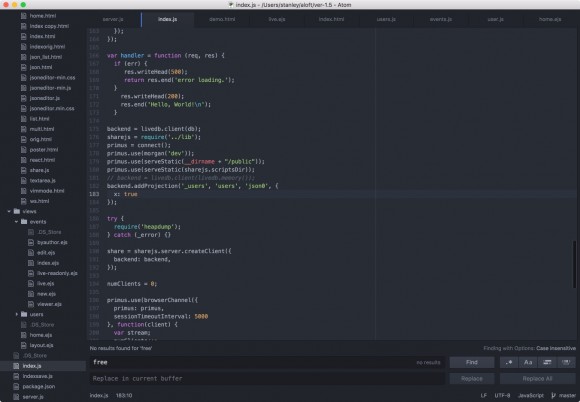

I decided to build Aloft for web so that any device with a modern browser could run it without complications. The core server is written in Node. I used Express and EJS to handle routing and layouts, and JQuery with JavaScript for handling the dynamic front-end bits.

I incorporated the ShareJS library to handle realtime communication, using browserchannel as its WebSockets-like interface. Additionally, I wrapped ShareJS with Primus for more robust handling of disconnects and dissemination of updated content if/when a dropped machine comes back online. Transcript data is stored in a Mongo database via a wrapper, livedb-mongo, which allows ShareJS to easily store the documents as JSON objects into Mongo collections. On the front end, I used Bootstrap as the primary framework with the Flat UI theme. Aloft is currently deployed on DigitalOcean.

Current Features

- Fast AF™ text delivery that is as close to realtime as possible given your connection speed.

- OS agnostic! Runs on Mac, Windows, Android, iOS, Linux, anything you can run a modern Internet browser on.

- User login which allows captioner to create new events as well as visualize all past events by author and event title.

- Captioner can delete, modify, reopen previous sessions, and view raw text with a click of a link or button.

- Option to make a session collaborative or not if you want to let your viewers directly edit your transcription.

- Ability for the viewer to easily change font face, font size, invert colors, increase line spacing, save the transcription as .txt, and hide menu options.

- Easy toggle button to let viewers turn on/off autoscrolling so they can review past text but be quickly able to snap down to what is currently being written.

- Ability to run Aloft both over the Internet or as a local instance during cases in which a reliable Internet connection is not available (daemonize using pm2 and access via your machine’s IP addy).

In the Works

- Plugin that allows captioners using commercial steno software that typically output text to local TCP ports to send text to Aloft without having to focus their cursor on the editing window in the browser. Right now, Aloft is mostly ideal for stenographers using Plover.

- Ability for users on commercial steno software to make changes in the transcript, with changes reflected instantly on Aloft.

- Ability to execute Vim-like commands in the Aloft editor window.

- Angularize front-end elements that are currently accomplished via somewhat clunky scripts.

- “Minimal Mode” which would allow the captioner to send links for a completely stripped-down, nothing-but-the-text page that can be modified via parameters passed in to the URL (e.g. aloft.nu/stanley/columbia?min&fg=white&bg=black&size=20 would render a page that contains text from job name columbia with 20px white text on a black background.

That’s all I have so far but for the short amount of time Aloft has been in existence, I’ve been extremely satisfied with it. I haven’t used my commercial steno software at all, in favor of using Aloft with Plover exclusively for about two weeks now. Mirabai has also begun to use it in her work. I’m confident that once I get the add-on working to get users of commercial stenography software on board, it’ll really take off.

TL;DR

I was captioning a web development course when I realized how unsatisfied I was with every commercial realtime system currently available. I consulted the instructors and used what I had learned to build a custom solution designed to overcome all the things I hate about what’s already out there and called it Aloft because it maintains the avian theme of the Open Steno Project.

Try it out for yourself: Aloft.nu: Simple Realtime Text Delivery

Special thanks to: Matt Huntington, Matthew Short, Kristyn Bryan, Greg Dunn, Mirabai Knight, Ted Morin

Stan’s Quick and Dirty Video: How Steno Works

Hey! Sorry for the lack of updates. But I wanted to share a new video I just made about how steno works for those who still don’t know. I wanted to make a very quick video that summed up all the main points in a way that was short and to the point so one of my students could use it for a class project about what it’s like in the day of a deaf person. Enjoy!

A Different Kind of Steno Hell: German

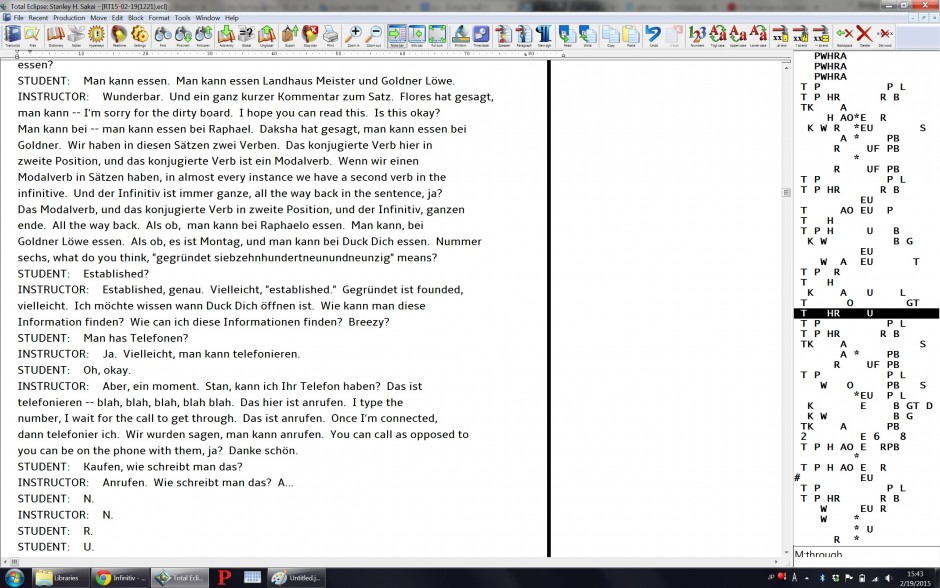

If you’ve missed the blatantly self-promotional vomit I’ve been unabashedly spewing all over Jade’s Stenoquery and on my own social media pages, you might not have known that I have accepted quite the unique challenge this semester: Captioning a semester-long intensive German class. I feel like I can barely manage to pull my head out of my ass when writing English realtime, but GERMAN?! HOW DO YOU EVEN? Besides not speaking the language at all prior to starting the class, stenoing a language class as opposed to a monolingual foreign language environment presents a number of unique problems that compound on the scads of details that we stenos are constantly juggling with in our heads whilst taking down just one language.

Let me explain why this situation is, without exaggeration, a venerable shitshow.

1. Language classes are bilingual environments.

You’re dealing with two sets of vocabularies and trying to prevent their corresponding dictionaries from overlapping because you constantly need access to the entirety of each at all times. You might be tempted to assign EUBG for “ich” but that’s your -ic. Sie and sie? Well, SAOE is “see” and SAO*E is “sea.” ES can’t be “es” because ES is “he is.” TKU can’t be “du” because it’s “did you.” The list goes on and on. How the hell do you brief anything? If you’re a brief heavy writer like I am, pretty much all simple strokes are used up, including those containing the asterisk. What is one to do? I guess I don’t have that many strokes containing the number bar.

Solution: NUMBER BAR IT IS. Thus, ich = #EU, ich bin = #EUB, du = #2KU, sie = #150E, Sie = #150*E, etc. Thankfully if it’s multistroke, the German entry will seldom conflict with an English entry so for those you can just write them normally. TKPWE/SEUBGT for Gesicht won’t really conflict with anything in English. Nor will PHAOURT/HREURBG/SAOEUTS for mütterlicherseits.

Sometimes, I just define the English outline for certain words that look enough like English and mean the same thing in German, which, consequently means that while I’m writing, random German words sometimes pop up. But since they look enough like their English counterparts, I don’t worry about it being confusing. It just looks kinda ugly having English text with random capitalized nouns and German here and there: “I have a nice Präsentation for you today. But before that, kann you all turn in your completed Handouts?” But you can only do so much, ja?

2. Special characters.

It’s logical to expect heavy reliance on fingerspelling in a foreign language class but what if the word contains a vowel with an umlaut or the eszett (ß)? These letters make important morphological distinctions in German. “Bruder” is just one brother but “Brüder” is plural. Es gibt hier ein Apfel aber ich kann noch drei Äpfel in meiner Tasche haben (There is an apple here but I can have three more apples in my bag). You can’t just stick in the non-umlauted version because many words differentiate themselves solely by the presence of the two dots.

Solution: Make additional fingerspelling letters using some random ass combination of letters. I chose STK* for no reason at all. Thus, STKA* = ä, STKO* = ö, STK*E = ë, STK*U = ü, STK*S = ß, STKO*EU = äu.

3. German phonology doesn’t necessarily map neatly to what we have available on the American steno keyboard.

There are many ways in which German does not “fit” on the English-derived steno keyboard.

- German has more vowels than English and many words are minimal pairs based on a vowel sound alone. Bruder/Brüder, schon/schön only differ by the raised vowel but some differ by a vowel and maybe something else attached to the end: Zahn/Zähne, Satz/Sätze. English steno theories do not have ways to handle these.

Solution: Reassign English steno combos to German values. Thus, AOU -> ü (Bruder = PWRURD, Brüder = PWRAOURD). AE -> ä (Satz = SATS, Sätze = SAETS). OE -> ö (schon = SHOPB, schön = SHOEPB).

- German contains certain consonant combos that don’t exist in English: schreiben, schlappen schneit, schwarz.

Solution: Again, make some shit up. SKHR- = schr-/schl-, SKPH- = schn-, SW- = schw-. Thus, SKHRAOEUB = schreib-, SKHRAP = schlap-, SKHRAF = schlaf, SKPHAOEUT = schneit, SWARZ = schwarz.

*I haven’t yet found an instance where having both schr- and schl- represented as SKHR- would create conflict.

- German morphemes don’t look like English ones, which makes tucking endings and such impossible using conventional English steno theory (The most common endings are not -ing, -ed, and -s/es so you can’t just throw those in intuitively for inflected forms). This fact makes writing German on an English steno machine incredibly sucky because PRACTICALLY EVERYFUCKINGTHING in German has mutable endings or vowels carrying fake IDs.

So how do you avoid having to come back for every damn inflection of a word?

Solution: Assign new values to final consonants that would serve as tucked endings in English. -DZ = -en, -Z = -e, -SZ = -es, -T = -t, *S = –st. Why -Z for -e? Jacked that shit straight from German steno. Thus, HABDZ = hab + en -> haben. SAGDZ = sag + en -> sagen. TRAGZ = trage. TKPWHRAUBZ = glaube. TKPWHRAUBDZ = glauben. If -Z doesn’t “fit” when adding -e, throw in * instead. So dachte becomes TKA*BGT, brachte becomes PWRA*BGT because you can’t fit BGT and -Z in the same stroke, obvs.

But you can have fun with this like in English. Make up a bunch of arbitrary shit that adds endings or phrases if it’s included in a stroke. Like, I’ve made the -Z into an x + Sie phrase ender. So haben Sie becomes HAEBZ, stehen Sie becomes STA*EUPBZ, können Sie becomes KO*EPBZ. -FB and -FT add the accompanying conjugations of haben in certain phrases. Ich habe -> EUFB, wir haben -> WEUFB, sie hat, er hat -> SWRAOEFT, EFT.

- Condensing syllables.

The reason there’s an asterisk in stehen Sie and können Sie in the above examples of phrasing is because it means I’ve “skipped” a syllable. So, like, kön-nen is KÖN and ste-hen (which is pronounced more like “shtay-hun”) is STAIN. I don’t really have a nice, concise system yet but for now I use * sometimes to condense two syllables, one of which contains a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed schwa-sounding one.

Stehen -> STA*EUPB, können -> KO*EPB, sehen -> SA*EUPB, gehen -> TKPWA*EUPB.

3. Capitalization.

German capitalizes all nouns. Ein Gewitter is “a thunderstorm” while es gewittert means “it is thunderstorming.” Sometimes a noun and a verb stem look the same. Sie fragen means “you ask” but haben Sie Fragen? means “do you have questions?” So every time I write TPRAG, which I’ve defined as “frag-,” I have to take a split second to ask myself whether in this context, it is a noun or a verb to decide if I should hit KPA (cap next) right before.

Say a normally capitalized noun is combined into some compound — yeah, it’s no longer capitalized if it’s not the first word in said compound. “The restaurant” should be written das Restaurant but if you want to say “my favorite restaurant is,” it takes on the prefix Lieblings-. Hence, mein Lieblingsrestaurant ist would be the German equivalent.

This becomes a problem if, say, you’ve made a handy prefix HRAOEBLS for Lieblings-. Eclipse doesn’t have a “force next word to lowercase” command so if you just write having defined RAURPBT as “Restaurant,” you get LieblingsRestaurant — wrong.

Solution: Define everything that’s a compound. Fingerspell like a mothafucka. Define certain things that are commonly said as non-nouns lowercase, that way you can just throw your cap next stroke in before it to make it look right. But the trick is remembering to every-goddamn-time.

4. Not knowing the language.

Most anglophone stenos will tell you (usually with a characteristic balls-out, no-shame, pedantic/elitist/prescriptivist flair — note to U.S. court reporters: Please stop) how crucial having a vast vocabulary is when taking down English speech. Well, lucky you because your English is pretty on point, yeah? Too bad it means koala shit in this context. Of course there will be certain frequently used words and phrases that overlap with English (Think: Schadenfreude, Zeitgeist, gesundheit, etc.), but for the most part, German phonology and syntax differ enough that having an exquisitely developed ear for English will help nichts bis sehr wenig when writing German steno, or any other language steno for that matter.

I have a fairly extensive linguistic background. I graduated from UW with a degree in Linguistics, speak three languages fluently, and have studied four others to varying degrees but German is not one of them. I speak intermediate level Dutch, which I’ve come to learn, resembles German a great deal more than English. It may sound like I’m bragging but all of this, surprisingly, makes little difference. It’s still hard af. For all intents and purposes, I’m as much a beginner as most of the other students in class. The class is mostly taught in German. While the other students can sit there clueless when the teacher says something unfamiliar, I have to get something down. While the others can use class time to practice new words and phrases, I have to have them mastered by the very next time the teacher utters them. I have to constantly draw upon my linguistic knowledge and combine it with what I can infer based on my cute repertoire of German to approximate spellings for the relentless barrage of words I’ve never heard before. I feel constantly under pressure to stay 10 steps ahead everyone else through intense self-study and/or keeping my phone unlocked with Google Translate up at all times.

One of the ways being a learner has become most painfully apparent is when attempting to accurately transcribe German declensions. If you don’t know what declension (also known as “cases”) is, it’s basically a way certain languages handle grammatical roles in sentences. While analytic languages like English or Chinese rely heavily on word order to convey who does what to whom in a sentence whilst leaving most of the superficial aspects of the words alone (their sound and spelling). Synthetic languages like German tend to do this by forcing you to solve a timed Rubik’s cube every time you hit a noun. Run out of time? Congratulations, you sound like an idiot. English has remnants of a more case-heavy past in the form of subject vs. object pronoun pairs: He/him, she/her, I/me. Well, German has three genders, two numbers, and four cases. So at minimum, an article will generally have 16 forms. Some look the same superficially but serve different functions. The masculine nominative der (the) is the same as the genitive plural — der! It makes word order relatively free compared to English but the drawback is that trying to compose a simple phrase in German is bit like attempting to haul all 20 of your rabid feral cats in a red wagon across a busy intersection.

Sie trägt den Pullover

- SWRAOE/TRAEGT/TKEPB/PHROUFR

- She is wearing the sweater.

Der Pullover ist grün

- TKER/PHROUFR/KWR*EUS/TKPWRAOUPB

- The sweater is green.

Ich habe einen Hund in meinem Haus

- EUFB/OEUPBD/HUPBD/TPH/PHOEUPL/HAUS **maybe make TPH*PLD in meinem??

- I have a dog in my house.

Mein Hund ist im (in + den = im) Haus

- PHOEUPB/HUPBD/KWR*EUS/KWREUPL/HAUS

- My dog is in the house.

Das ist ein Haus

- TKAS/OEUPB/HAUS

- That is a house.

Wofür interessieren Sie sich?

- WAOUFR/SPW*/SAOERPB/SWRAO*E/SEUFP

- What are you interested in?

Woher kommst du?

- WOER/KO*PLTS/#2KU

- Where are you from?

Ich komme aus Seattle.

- #EU/KPHA*US/SAOELGTS **Notice I phrased komme aus as KPHA*US. The * is supposed to stand for the -e in komme.

- I come from Seattle.

The bolded portions of the above examples are to point out the various forms words like “the,” “a/an,” “my,” and “you” take in German. The last example is to illustrate how I applied both phrasing and inflectional principles into a single stroke.

On top of that, Germanic languages tend to stress the first syllable so a lot of times, unless a phrase is uttered very carefully, it’s hard to tell the difference between eine, einer, einen, einem, deine, deiner, deinem, kein, keine, keiner, keinen, keinem because the first syllable gets the stress and the rest goes straight to schwablivion.

Q. So what does all this amount to?

A. Some ridiculous fucking crazy shit.

The end. Tschüss (STAOUS)!

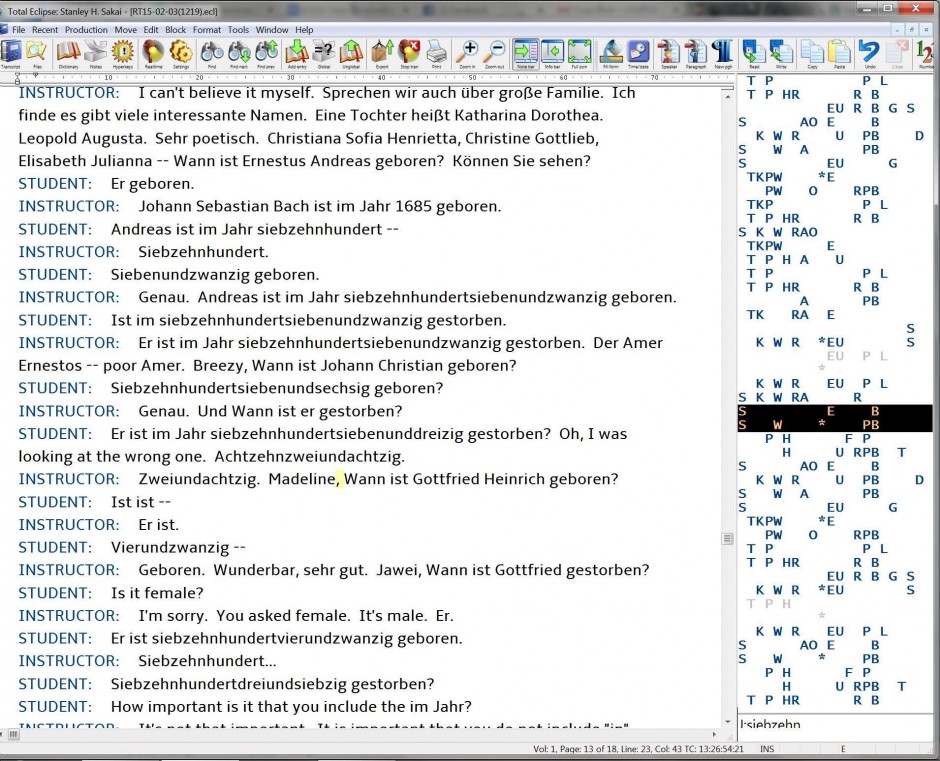

Pics From My Talk @ PyGotham 2014!

Reporters, Not recorders

After reading this lovely article by Kelley Lord wherein she describes the struggles associated with her experiences as a server in a cruel world, I was inspired to come up with a similar list, but having to do with stenographers, of course! I realize that stenographers are a fairly esoteric bunch — “misunderstood” doesn’t even begin to cover it. So it seemed to be a fitting theme for a blog post. As a disclaimer, I’m writing this from the viewpoint of a realtime captioner. Court reporters work under slightly different circumstances and I won’t delve really into the differences.

Without further ado, Reporters, Not Recorders: 5 Things Your Stenographer Wished You Knew

1. Don’t call what we do “typing.”

Many people make the false assumption that what we’re doing behind our funky little keyboards is essentially listening carefully and “typing” what we hear. Easy, right? In reality, it is far more complex. Typing involves recalling a word’s spelling, tapping out the correct sequence of letters, hitting the space bar and shift keys occasionally, and managing to not get your thumbs lodged in your anus during said process. God help you if you happen to spill your coffee in your lap and you have to backspace the mistakes you made while fumbling, trying to pick your doughnut up off the floor.

Now as stenographers, we don’t have time to drop our doughnuts or make errors as our job requires us to keep up with somebody else’s speech. That changes the paradigm a bit since now, you’re not only having to get it all down correctly the first time, but you’re having to do it as fast as somebody who isn’t you decides to deliver it. Not to mention, the process of writing steno requires that we hear a phrase, break it down to its constituent words, recall the corresponding shorthand outlines (which look like gibberish to you normal folk), execute those outlines with nearly 100% precision on a completely unique keyboard layout in order for the computer to correctly match them against our personal dictionaries, all at around speeds of two to five syllables per second. This is how it looks in action. We press multiple keys at once to capture handfuls of phonemes at a time, forming entire syllables every time we press down. There is no magic auto-correct or any form of predictive entry, auto-complete, Siri voodoo nonsense. Some modern steno software have algorithms that will try to guess, phonetically or statistically, how sloppy or otherwise malformed steno should have translated but worthy stenographers cannot and do not rely on this. Good realtime (instantly readable, machine-translated steno) is the product of quick and nearly perfect recollection and execution of the entries in one’s personal dictionary. I liken our job to sitting in front of a piano and having someone constantly put new pieces you’ve never seen before in front of you, demanding you play them at full concert speed with 99% accuracy. The preferred terms when referring to a working stenographer are “writing” (from “writing shorthand”) or “stenoing.” So please don’t refer to what we do as “typing” as it would be a shame if you were to trip and fall over a strategically misplaced piece of equipment before the end of the proceeding.

2. We’re not robots and we’re not psychic.

As Dee Boenau puts it, “we [stenographers] have to be very worldly” in that our work requires us to competently take down conceivably any topic thrown at us. We’ll try our best if you unexpectedly delve into the works of Feyerabend, discuss the plausibility of a working Alcubierre Drive, or on a whim, prattle your way into Sorites’ Paradox, GroEL/GroES, the P1-N1-P2 complex, maybe the historical significance of Nyan Cat, or the current exchange rate of the Dogecoin. But we can’t know everything all the time and the occasional error is bound to happen. And although most of us practically become walking, breathing encyclopedic databases of random knowledge over a career span, realize that we are still not Watson and giving us a list of key terms beforehand is immensely helpful. You see, what we stenographers do is we program shortcuts into our steno lexicons in advance so that we can pop out anticipated phrases or terminology quickly, usually via a single-stroke shortcut that we come up with on the spot. So even for what seems “basic” to you, giving us a heads-up for little things like, “Oh, by the way, Jacqui sitting on the left spells her name J-A-C-Q-U-I and her last name is Kaminsky” or “We’re going to be talking a lot about indigenous fauna, like x, x, and x” takes a HUGE load off our shoulders as we can then go ahead and redefine our steno outline for “Jackie” to render with her preferred spelling and quickly stick in briefs for “indigenous” and “fauna” to have on hand as they come up. It just makes things go a lot smoother for us. As the person who makes your dialogue magically appear in text form next to your PowerPoint for everyone to see, I have a lot of power. But with great power comes great responsibility and I will thrust part of that responsibility onto you, speaker and/or event organizer, of ensuring the captioner is informed of any tricky names or terminology. If we flub something due to your failure to inform us and something funny goes up on the big screen, I’m just going to go ahead and say, “Nice job, idiot. It’s all your damn fault.” ;]

3. Stop talking over each other!

I have a little exercise for you. Type me a verbatim transcript of this eight-second audio clip taken from a VSauce video.

Got it? Cool. Assuming you have normal hearing, a working short-term memory, can type, have a computer that can play the clip, and understand English, it shouldn’t be too difficult.

Now transcribe this one.

Wasn’t that fun? Now imagine doing that for two hours.

One at a time or I torch this mother to the ground with your motor mouth in it, k? Thx.

4. Remember to breathe and enunciate.

The average, non-cocaine-abusing English speaker speaks at a rate of around 150-180 WPM. 180 WPM sounds like a pretty comfortable pace to most native speakers. The baseline requisite speed to become a certified stenographer in the United States is generally set at 225 WPM for English at 95% accuracy. The best of us can go much higher than that, sometimes exceeding 300 or more WPM in bursts. So, yes, as licensed stenographers, we are trained to go FAST. But please, give us a break and slow down once in a while. Maybe add in some tasteful pauses?

Now I understand it isn’t easy to change your speaking habits. I find that most speakers are completely unaware that the way they speak is, well, really quick, and that they’ve had their foot planted firmly on the stenographer’s submerged head for the past two hours. And even after a polite reminder to maybe slow down, most people relapse after about ten minutes and it gets awkward having to repeatedly remind people to monitor their speech as people tend to become very self-conscious. So if you could maybe remember this and possibly, pretty please, with a cherry on top kick it down two notches and try to make an effort to keep it there? But more than just unrelenting speed, the number one thing that makes me want to drown the speaker I’m taking down in the river of blood from my rage-induced fit of harakiri is mumbling. I can go fast but if I have to strain to understand what you’re saying, those split seconds of hesitation add up and REALLY make it a struggle for me to maintain a rhythm. Oh, and if you’re talking so fast that you start mumbling because you physically can’t pronounce the words that quickly without getting your tongue caught in the ceiling fan? Yeah, I hope as you’re drowning in that river of blood, you trip over the strategically-misplaced tripod into a bed of rusty nails covered in cat urine.

5. A little acknowledgement never hurt.

Please, do take the time to talk to us. We’re friendly, most of the time and — surprise! — people, too. After working behind the scenes for so long, Norma and I were really spoiled by you wonderful folks at SRCCON. It was a welcome and unexpected novelty as stenographers to be put front and center for the entirety of the conference. We really appreciated it and we joked amongst ourselves that our heads would never return to normal size. But really, just asking how we’re doing or if there is anything you could do to help make our lives easier is appreciated. We don’t ask for much. Give me a comfortable, armless chair, an extension cord, and maybe a few snacks and we good. Anything beyond that is extra but for us stenographers, the distance between “apathetic” to “LOVING YOU” is small and any effort on your part will win us over and cause us to casually kick that tripod back under the table :].

5 Things New York City Has Taught Me

As a disclaimer, I’d like to first say that despite the descriptions of my experiences that, at times, could be interpreted as sounding negative or tragic, that overall, my new life in the City has been overwhelmingly positive. This is just my overly frank analysis of my circumstances as I am apt to do with all things.

Five Things New York City Has Taught Me: A Six Month Reflection

(As a twentysomething, recent inductee into the NYC scene)

1. You will meet people in the most random places.

It’s true. It’s logical that in a city of 8 million, it’s bound to happen. But I am continually surprised by how people I run into at the gym, the park, the club, on Tinder, or on my way to the subway unknowingly and suddenly become permanent fixtures in my life. Take advantage of it and keep yourself open. You never know what can happen.

2. Life will pass you by if you don’t look up.

Despite how horrible sometimes it can be not having an excuse to avoid awkward eye contact during the moments we’re all trapped inside a steel tube, crammed inches from each other’s armpits, sometimes I find it beneficial that most of the time on the New York Subway, there is no mobile phone reception. For a guaranteed few minutes every day I am forced to be in the present, be it trying to figure out what language the passengers across the car are speaking or witnessing a drunken tragedy unfold before my eyes, the only things with which I have contact are those of the immediate present. All too often I have observed people living their lives completely oblivious to the fact they live in this great city, unable to take pleasure in really anything. I understand that a large portion of twentysomethings move here for the expressed purpose of complicating their lives in pursuit of their ideals of becoming the archetypal fast-paced New Yorker busybody that everyone needs at all hours of the day but nowhere, I feel, is a higher sense of awareness more beneficial, or even requisite than when living in a place like this. Unless you can step back and detach, the City will suck you in and put you in a sensory coma. Instead of silently bitching to yourself how shitty the MTA is every time your train is late, why not take a moment and look at your surroundings. Has it even crossed your mind how much history and engineering had to have to come before your being able to stand there, pissed that the E is taking forever at rush hour? But I guess if you’re legitimately about to be late for something, fuming and seething with frustration is the most appropriate response. Still though, New York is fucking awesome. These moments will make up an amazing chapter in your life. Don’t let them slip away unnoticed.

3. If you haven’t already mastered self-restraint, you will learn the hard way.

In a city where time is relatively scarce, and where you can’t walk a block without passing by a restaurant, a bar, a shop or four by the time you reach the next intersection, if it isn’t the variety, the accessibility will test your self-restraint to its limit. Then throw in your revolving circle of acquaintances who all invite you to happy hour at all hours of the day, who the hell wants to stay in and cook? For about a month and a half of living here, I only ate out or ordered Seamless out of convenience. But now, I eat out maybe once a day if it’s a particularly long day out and about working. On weekends, you will face an unyielding barrage of temptations to go out. Well, this depends on the people with whom you tend to associate but for me, as someone who exists in the overlap of both the EDM and gay scenes, the allure is particularly unrelenting. If it isn’t a favorite DJ, it’s your bar/club buddies who cordially request your presence in becoming shitfaced. Going into it knowing you don’t live in a world with unlimited resources is a good start, lest you wake up one morning to check your bank account in horror after you’ve finished puking up all the pills and shots from the night before.

4. You will become acutely aware of rude or inconsiderate behavior and may become more considerate as a result.

What I’m thinking as a New Yorker:

- That person walking super slowly in front of me with a million bags weaving left and right: What the fuck is this fucking bitch doing? EITHER MOVE THE FUCK OVER OR LET’S GO.

- That person who’s smoking next to me, conveniently located where the wind will blow it all in my face: At least your stupid ashtray cuntface is gonna die early. Seriously, fuck you.

- This person who is deafening me with their furious honking because they decided to go right before the light changed and is now gridlocked: Hey, dickcheese, not my problem you’re now blocking all of 6th Avenue, so shut the fuck up you fucking piece of Jersey shit.

Makes sense since we New Yorkers are so constantly rude, right? Not so fast. Basically, it comes down to the fact that since we’re all so tightly packed together, any act performed on your part without due regard will affect at minimum, the ten people immediately around you. And so it’s not that New Yorkers are rude, as conventional wisdom may imply. In fact, people who actually live in the City are quite pleasant to be around because they understand the unwritten code of urban living. Those who live here understand how to navigate tight spaces without getting in the way and, in public, behave in a way that maximizes efficiency given the limitations in real estate and time. Be swift and move confidently. If you fuck something up, most New Yorkers will smile and won’t think anything of it if you apologize. Act obnoxiously, and prepare to be shoved, knocked in the shoulder, eye-rolled, scoffed, or even yelled at. Oh, and if you hold a subway door, be prepared to have your arm chopped off.

5. You will learn who your true friends are and will value your time with them more than ever.

I saved this one for last because despite the blissful optimism I look to New York City as this new chapter of my life unfolds, this is the one theme I longingly look behind to my days in Seattle with stinging nostalgia.

Since I moved to New York, my social network has exploded and yet, there has never been a time I’ve felt more alone as I have felt here. Part of it has to do with the actual literal geography that separates me from my family and friends from earlier times. As a native west coaster, I’ve never in my life been so far from my roots. But a big part of it, I notice, comes from just the pace of NYC and the culture of social interaction here. I dub New York City, The City of Acquaintances, as they seem to abound in every sphere of my life — acquaintances who will drink with me, go out with me, have cursory conversations with me over brunch or over Facebook or text. We will party, share stories like friends, and at least superficially, appear to share a bond not unlike a “friendship.” Yet at the end of the designated social gathering of sorts, we part, never to talk to each other except on occasion to plan the next designated social gathering, or at the next gathering itself. They are context dependent colleagues, like actors in a play if these social gatherings were shows. Certain people to go out with, certain people to have midday lunch with, people to meet for dinner, people to work with, people to fuck, people to go shopping with. Like in a play, everyone is assigned a specific role. Once the show is over, the characters bow, and the setting dissolves into no more until the next one.

Why is this so hard here? You know, having true friends who will tag along to dinner with a last minute text. The ones who will show up drenched at your door to console you when it’s pouring outside after some boy rained all over your heart. The ones who, with nothing better to do will stay in, bake cookies with you, get hammered, play video games, and call it a great night. The ones who will turn up with you at a rave but will leave with you if you were having a bad time no matter how much they were into it. The ones who keep your toothbrush and deodorant at their place because you stay over so much. The ones who will stay up talking with you all night and leave at 3:00 in the morning on a Sunday night. The ones who will sit in front of you at a coffee shop somewhere with their laptop, while each of you do your own thing. Yet both parties feel a sense of comfort and satisfaction as a result of the other’s presence. The ones who buy you presents for no reason. The ones who don’t flip endlessly through all their acquaintances whom they could avail when deciding who will best fit the role for “friend” at this particular free moment. The ones who don’t need a plan to be available. The ones, who in the absence (or abundance) of pretty much anything else, will default to you.

While most of the time efficiency is the way to go in New York City, this is a huge exception. I admit that having associates for every particular occasion, and only that occasion is convenient and logical when faced with a seemingly endless revolving door of people coming in and out of your life in a city as big as this one. It takes time and resources, both of which the majority of people here guard fiercely with miserly custody, to invest in somebody when the possibility looms that at any given moment you could find somebody with higher social capital: Better looking, more affluent, funnier, better connected. But I urge you, New York, this is not the way to go. I’m not sure if this is due to a difference between the coasts or maybe even a difference between making friends as a college student versus as a working professional but as far as I’m concerned, New York has taught me that perhaps the very definition of “friendship” may not be universal. And I’m sure you can imagine what my dating life must be like here if you extrapolate what I said above re merely finding friends.

But actually, I think what New York has taught me about intimacy is that no matter what, in the end you have to be okay with yourself. Because no matter what happens around you, or who comes into your life or departs, even if no one fulfills your definition of what a friendship/relationship is or even wants to, as long as you can stand strong by yourself, you’ll be okay.

And even though I’m still waiting to have here what I had in Seattle, that’s okay because until I do, I have me.

Can’t Sleep

Normally I don’t take articles from Cracked.com too seriously but this one hit home in a special way. So. Fucking. Spot. On.

5 Awful Side Effects of Insomnia No One Talks About

You see, I have insomnia.

Most of the time when I tell people I’ve gotten maybe 12 hours of sleep the entire week, they probe me for explanations or simply tell me to just go to bed earlier. Or maybe, try stretching, yoga, chamomile tea, melatonin, warmed milk. Whatever they suggest I do, I probably tried it last night. Sometimes they offer me empathy.

“Yeah, a couple nights ago I had really bad insomnia. Like, I got three hours of sleep and work sucked ass the next day.”

“Well, how do you feel now?” – I ask.

“Oh, I came home and took a nap for, like, two hours, had dinner, then went back to sleep until morning.”

Lucky you.

Is it really that easy for everyone else? Is that why they make fun of me or react with disbelief when I tell them that I normally sleep for 10-12 hours each day on the weekends, normally not waking until about 3:00 pm?

Try having it be a daily struggle.

Endless tossing until 5:00 in the morning, feeling overheated and antsy. Take the covers off and you’re too cold. Pull the blanket back on and you dampen the sheets with your own sweat. No matter how you turn, shuffle, or contort your body, there’s somehow always an itch, a twitch, a weird pain somewhere just annoying enough to compel you to flip, waking yourself up all over again.

Sitting upright at 4:00, feeling partially defeated, wondering if it would be worth it to try taking another sleeping pill or to pull another swig even after having slept just four hours the night before.

“Oh, you get to wake up at 9? That’s must be so nice!”

Not if you’ve been passing out moments before sunrise in a chemically-induced haze for the third time this week. Why? I don’t fucking know. I really never know or can control when my body feels like sleeping or being wide awake and anything that happens to me before 1:00 pm is pretty much miserable – a blur of resentment, nausea, inability to focus on anything for more than two minutes, and wondering why the fuck this bitch talking to me right now is so damn energetic. IT’S 8:30 IN THE FUCKING MORNING. I SHOULD BE IN BED RIGHT NOW. STOP TALKING TO ME.

And truthfully for the four to five nights of the week I do manage to achieve some semblance of somnolence, I don’t “sleep” as much as pass the fuck out from complete exhaustion, and, oh, mixing sleeping pills with alcohol. I lay helpless and distraught. I have no control over my own body. How is it that I just took six sleeping pills and yet feel nothing?

I grab my phone and check the time.

“I have to be up in four hours”

I check Facebook.

“I have to be up in 3 hours”

I check Instagram, OkCupid, Tinder, okay, Facebook again. A round of Angry Birds? PvZ? What the fuck am I doing?

“Fuck, I have to be up in an hour!”

At a certain point I know I’ve lost.

“Fuck it. Just fuck it.”

I arduously crank the knobs in the shower wanting to die.

On nights like these, I think about Michael Jackson – how he abused propofol until he basically put himself to sleep forever. And then I imagine how handy it must have been to have such a high-powered general anesthetic like that on hand, fantasizing about using it on myself with the same ardor and titillation a bullied kid might daydream of the day he finally brings a gun to school.

Bedtime for me is a time of anxiety, uncertainty, and ultimately, dread.

Save the odd night or two, you lie down most nights and simply drift off without thought.

That, my friend is a luxury.

You don’t fucking have insomnia.

By Popular Demand: How I Got Into Stenography

This post was originally my response to an email I received regarding teaching oneself steno. I figured it was about time I write the whole story in one place so I can stop telling the same story over and over again and also because I owe Mirabai my “How Plover Ignited My Career in Professional Stenography” article I’ve promised her for, I think, two years now. 😛

The original email asked:

I’m really interested in learning to caption, and would like to hear how you taught yourself because I could sure skip the $$$ of court reporting school/courses at this point in my life. I also have a linguistics background and wonder how much that might help? How much time did you spend at it, etc.

My response:

I’m glad you are looking into teaching yourself steno. I am currently mentoring a friend who lives near me in learning machine shorthand. She, too, recently acquired a machine and wants to teach herself.

Getting Started/Plover

I started my journey learning stenography by teaching myself Gregg shorthand in university and got really fast at it in a very short amount of time. This was strictly for the purpose of keeping up with instructors in class when taking notes. When I took computer programming, there were actually multiple deaf students in the class because it was for the Summer Academy, a sort of grant-funded scholarship sort of program whereby the UW will let deaf or hard of hearing students take classes for free at UW related to tech and engineering. We had a captioner in every class hooked up to a projector and for the longest time I was in awe and had no idea how the system worked until I finally went up to the prof and asked how in the world could every word he uttered in class (along with every word uttered by the students in the class) go up in real-time on the screen.

“She’s doing it,” the professor says while glancing at the little lady sitting at the front I hadn’t noticed until then. She had a very strange-looking keyboard on her lap and I was fascinated, watching her effortlessly make a few taps that would expand into entire sentences at lightning speed on the screen. I eventually went up to her and asked how she operated that machine. So she then goes into machine shorthand and asks me if I’ve ever heard of pen shorthand. I don’t think she expected me to know what it was much less witness me whip out my notebook covered in Gregg and boast I could spit it out at 110 WPM after a couple months of self-study. She told me what she’s doing is just like Gregg and from that point on, I wanted to know more. I researched and found Glen’s website and Plover, a free, open-source stenography software that lets you steno using a gaming keyboard created by a brilliant team consisting of my stenographer friend and colleague in NYC, Mirabai Knight and software developers, Joshua Lifton and Hesky Fisher. As soon as I learned enough to get a few words up on the screen, it was all downhill from there (or “uphill?”) and I kept practicing on the gaming keyboard for fun and looking up any words I didn’t know how to steno in Mirabai’s stock dictionary.

Acquiring Professional Equipment and Software

I soon got my own Gemini machine from eBay for about 100 bucks and started practicing. I used it for everything – taking notes in class (yes, I lugged it around with me) to just playing around, listening to the TV, getting down as much as I could. At that point, I had downloaded DigitalCAT, a proprietary CR software whose company, Stenovations, offers freely for use by students of stenography. I would divide my time between ling classes and trying to incorporate steno into my routine as much as possible (writing essays, emails, etc.).

Steno Theory

Stenovations has a variety of starter dictionaries for download on their download page. I started with StenED as it was a theory I had seen mentioned online all the time, but quickly learned how stroke intensive it was. I switched to Phoenix, characterized by its vowel omission principle, the fact that all schwas were written with “U,” and its overall strict adherence to phonetic rules because in my mind, it seemed logical and facilitated “less thinking and more doing.” Well, that did turn out to be the case but not necessarily in a positive way. It was way too clunky and laborious for me. Having to write everything out in 3-4 strokes gets old fast. Granted, I could’ve just refined and modified Phoenix like some of my colleagues have to make it more efficient and usable (Jade King being a notable example), but in the end, I personally didn’t like it. And since I’m the only one who will be writing whatever theory I learn for the length of my career, to hell with it. So I scrapped it altogether.

FYI:

- Vowel omission principle: You omit vowels in sequential multi-stroke words, the idea being that it’s one less thing to worry about. So a word like “inhospitable” would be written something like TPH/HOS/P-T/-BL instead of TPH/HOS/PEUT/*ABL or something.

- Schwas written as U: Vowels that are unstressed are typically pronounced as an indistinct schwa sound in English. If you have to stop for a second to remember the spelling of a word, it might cause you to hesitate. By writing ALL schwas as U, you no longer have to worry about the exact identities of the vowels on the fly as in other more commonly orthography-based theories.

I finally switched to Philly Clinic Theory ’cause I heard it’s what Mark K. wrote before he, through his interpretation of it, made it into Magnum. Now, I write a combo of both Philly and Magnum but they draw on each other because Magnum is basically the principles of Philly modified somewhat and cracked out on briefs. Since I learned Philly, I often find that when I think of a brief for something and check Mark’s Magnum dictionary to see what he uses, I find we come up with the same answer independently all the time. But a lot of people tell me I “think” like Mark so it could be that. But based on my own introspect, I know I can memorize arbitrary sound combos (and movements as is the case when I started learning ASL) with ease and assign them meaning. I very seldom need a mnemonic or memory trick to make it stick. I say a lot of my being able to subconsciously remember thousands of briefs with little effort comes from my experience in being/trying to maintain (my status as) a polyglot having honed my brain to that kind of thinking for practically my entire life.

As far as Phoenix goes, I don’t like it. I like very short, efficient theories like Philly Clinic, or Magnum. I don’t know how your brain works, but like I said, I know how mine does. I can make random briefs here and there, do them once or twice during a job, and remember them all correctly at speeds upwards of 280 words per minute a year later. There’s no secret to that, either; it just happens for me. If it doesn’t for you, then you should consider maybe learning a longer theory with less of a memory load. I’m saying this with the assumption in mind that you don’t want to take forever before you start working.

A linguistic background may help you in that you were probably taught to be more descriptive and not as prescriptive like 99.99% of CRs are. I feel I spend less time agonizing over why somebody keeps using this verb wrong or doesn’t use the subjunctive than most other reporters because I don’t care. As such, I do not correct speakers when I write their speech. I only care about accurately portraying their utterances in text form, not whether or not it is correct prescriptive American English. I think being a polyglot or bilingual would help much more, especially for when you hear random words that are not English. A ling background also helps when I hear “post-alveolar affricate” in a ling class, but I know that wasn’t your question. It might also help you find patterns in how theories smoosh words, or syllables rather, into the rather small phonetic/phonemic template you have to work with on the steno machine.

As far as equipment all you really need is a machine that can output to a computer, either by serial connection, USB, or some other protocol. I mostly input my steno via Bluetooth at all times currently. Also, you will need some CAT software. CAT stands for computer-aided translation. It’s the program you run on your computer that takes the the steno input, compares it against your dictionary(ies), and outputs the text on the screen. You can use Plover as you’re starting out. Though, it’s grown to become quite powerful now, and I actually use it on some jobs where Eclipse would be too slow, or somehow otherwise unsuitable for the task. I foresee it becoming sophisticated enough to be used professionally all the time in the near future. There’s a job for which I’ve used Plover exclusively because their captioning system is not very good and requires the user to input the text directly into a box in a web browser and to press the enter key every line or so. Eclipse tends to be very slow at outputting to Windows and also formats things in strange, unpredictable ways when using its text output feature so I always go with Plover. In the future, I’ll probably be using Plover exclusively as professional software once it gains a couple key features.

Advice For Teaching Oneself Steno

The only advice that I can really give you is find as many ways to incorporate steno into what you do every day. People often ask me how I learned so fast, and how I was able to do it even though there are hundreds of steno students still in school for years and years while I step up to an invite to attempt the Guinness at the NCRA Convention after having only three years of experience from start to present learning/practicing stenography. I never took theory so basically I looked under “Stenotype” on Wikipedia and taught myself the substitution combos from their list and just found the stock dictionary off of DigitalCAT’s website and one-by-one went, “How do you write ‘rabbit’ in steno?” Or “couch,” or “chair,” or, “girder,” or “cell,” or, “chapel.” I kept doing that until I saw patterns and it all fell together in place. Also, I did quite a bit of poking around in my CAT software, just to see, “Ooh, what does this button do?” After that, it’s all about meticulous homing in on what your weaknesses are, and practicing the shit out of them, going through your dictionary and adding entries that you’re unsure if you have have or not. But most important is to keep practicing, practicing, practicing, and never giving up. Getting angry that something in a passage tripped you up, practicing it and/or briefing it, and coming back and killing it. Do that enough and you get good very fast. The biggest fault I see in today’s court reporting education is its seemingly complete inability to equip their students with the tools necessary to evaluate their own progress. CR students constantly ask others what they’re doing wrong, asking whether what they’re doing is right, when the answers lie right there in their steno notes. You just have to rifle through and find for yourself what you’re doing right and what you’re screwing up. Yeah, it sucks to have to go back and figure out what exactly you got wrong, compare your transcript to what it’s supposed to be, and rote drill the living crap out of whatever it was you got wrong. But it’s the only way. Again, there is no secret. Or maybe it’s the students themselves, I don’t know. But what I do know is far too many bash away at the machine doing the same thing over and over thinking that they’re going to get far through sheer amount of time racked up behind the machine. Not true.

Some instrumentalists end up playing in Carnegie Hall, while most of them either don’t have the discipline necessary, don’t want to put in the effort, or don’t have the right innate talent. Even for those who truly, truly WANT to do steno or play an instrument professionally, they may not possess the willpower that matches their desire to cross the finish line, however burning it may be. Some may put in the same amount of hours but never achieve the level of refinement of Mr. Carnegie Concert Cellist over here simply because he/she is not naturally suited for music. Life isn’t fair. Moreover, it could be any combination of the reasons I mentioned above that bar most players from attaining concert status (or in our case, from becoming professional, realtime stenographers) plus a myriad of other possible just “life” circumstances so it’s hard to answer the question why certain people progress faster than others.

So many people ask me, “What was your secret?” “What was your regimen?” “How did you practice?” “How many times a day did you practice?” ” How many hours did you practice?” I say, “2-4 hours a day maybe? Sometimes up to 12 hours?” “I don’t know, sometimes less.” “Sometimes, I didn’t practice at all.” “Most of the time I practiced to random shit I found on the Internet.” Then they’re confused ’cause to them it doesn’t make sense that someone who, in their eyes has achieved a great deal can be so unstructured and la-de-da. It’s because I’ve learned to find the exact things I need to work on, and work on them. If I’m already writing pretty cleanly at 180, why the hell would I keep doing takes at 180 for “accuracy?” I’m going to take that 190, 200, 225 head-on and kick it in the shins as hard as I can even though I’m still a foot too short. My time is limited. There are too many EDM festivals to go to, too many cities and lights to see, too many people to meet out there for me to sit here and waste away my numbered mortal hours being pre-employable.

But what if I have a husband? Or a Dog? Or children? Or a fulltime job?

Also, I remind people that they have to take into account that I’m not married, I don’t have children, I lived at home with my parents while I was practicing to become certified, and had no other job besides to practice. I believe that contributed greatly to the speed with which I went pro. People ask me what I would have done if I had children, or a job, or a house mortgage to pay, or whatever. I say, I don’t know because right now, I live in a studio apartment in the middle of the city by myself, and am living a pretty 20s sort of lifestyle.

I’ve never had that lifestyle, and I probably won’t have it for a long time. I knew going in that I had the time and the resources to be able to do this both intellectually and materially. Some people go in, and complain that they don’t have enough time to get in their practice because of husband, familial obligations, and “stuff.” So many students are begging for any help they can get, lamenting that they’ve tried everything and are either progressively slipping further and further into debt or are already so broke, they don’t know if they can afford yet another semester. This will sound harsh but at a certain point, one needs to make a judgment call, cut one’s losses, and realize it’s time to move on.

To me it was an easy answer. I knew could get certified without the structure of school because I know I naturally find steno fun, so I didn’t really need something or someone bearing down on me in order to practice. I would gladly do it on my own accord. I had my experience of learning Gregg to a usable speed very quickly. I already knew that I had the mental “arsenal,” so to speak, to tackle this kind of simultaneous translation sort of task. I used to want to become a pharmacist before I discovered steno. But at one point in university I made that judgment call – that, no matter how hard I work, I was just not suited mentally for the “lecture, review book, memorize random shit as fast as you can, knowledge-vom on test, rinse and repeat” cycle that a hard science field like pharmacy requires. I also suck royal balls at math, so yeah, no use killing myself trying to work against my programming when I have other talents I could harness. Like any other trade skill, not everybody has the “machinery” to do steno. It is why we are able to charge such a pretty fee for our services. It’s mentally taxing and requires a certain kind of wiring to be able to concentrate that hard for that long, parse speech that quickly, and by drawing from both declarative and procedural memory, convert it into a code that you execute with your hands. You need to be honest with yourself whether you can really go at this on your own because while it might sound great in principle, once you get to the 120 rut and the 180 rut, you might not have the wherewithal and focus to be able to fight through the discouragement.

So what now?

But my biggest take-away from all of this is just that there’s no secret. There is really no secret. There is nothing that I did differently than anyone else to get to where I am, other than maybe being much more critical about my abilities, finding creative ways to eliminate personal deficits by acquiring information on my own, and using the Internet as my resource to learn how to do everything. Or if there was no direct answer somewhere, deducing it by putting two and two together after researching related topics.

But that’s all I think I have to say for now.

If you want to be a steno autodidact (is that a word?) it pretty much comes down to thinking for yourself and self-motivation. If some shit ain’t workin’, Google that shit and figure out how to make it work. It’s really not that hard. Don’t go looking for the “secret” to gaining speed; you won’t find it. If you really want something, you’ll find a way.

Good luck!

Stan

![Stole one of these. ;]](http://blog.stanographer.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pygoth6-940x626.jpg)